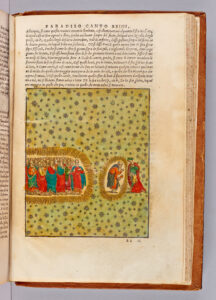

We are in the heaven of the fixed stars, which the pilgrim entered at verse 111 of Paradiso 22, and now Dante will be examined on the three theological virtues: faith, hope, and charity. His examiners are “the three Jesus favored above the rest”: “quante Iesù ai tre fe’ più carezza” (Par. 25.33). In other words, his examiners are the three major apostles: Saint Peter will examine Dante on faith; Saint James will examine Dante on hope; and Saint John will examine Dante on charity, aka love.

Paradiso 24 is devoted to the examination on the first of the theological virtues, faith. Here, in sharp contrast to Paradiso 23, the discourse is logical, linear, and scholastic to the point of being legalistic. As I note in The Undivine Comedy, Paradiso 24 is the only canto in the poem to contain both the verb “silogizzar” (77) and the noun “silogismo” (94), neither used disparagingly.[1]

If the textual emblem for Paradiso 23 is the phrase circulata melodia, the textual emblem for Paradiso 24 is the adverb “differente- / mente” (Par. 24.16-17). The second and final presence of the adverb differentemente in the Commedia (the first is in Paradiso 4.35) also constitutes the poem’s only instance of a single word divided by enjambment between two verses. Here Dante turns enjambment away from its unifying function in Gabriel’s song and focuses instead on the trope’s divisive properties, performing the concept of difference in “differente- / mente”’s very appearance. He thus signals the discursive shift away from the mystical circularity of Paradiso 23.

Another indicator of the discursive shift toward a more linear and rational style is the famous simile of the bachelor student who prepares himself for questioning. As compared to the similes of Paradiso 23, which engage the reader affectively in such a way as to impress a feeling, rather than to tell a story, the simile of the baccialier is quintessentially non-lyric. It belongs to the narrative mode and in fact constitutes in itself a little narrative, a brief but recognizable story with a logical structure:

Sì come il baccialier s’arma e non parla fin che ’l maestro la question propone, per approvarla, non per terminarla, così m’armava io d’ogne ragione mentre ch’ella dicea, per esser presto a tal querente e a tal professione. (Par. 24.46-51)

Just as the bachelor candidate must arm himself and does not speak until the master submits the question for discussion—not for settlement—so while she spoke I armed myself with all my arguments, preparing for such a questioner and such professing.

Logical structure is everywhere apparent in Paradiso 24, which proceeds clearly and rigorously from point to point; Dante wants to exemplify a syllogistic form of reasoning that manages to be precise and yet untainted by sophistry.

How fascinating that this logical and rationalistic canto is devoted to a demonstration of faith! In Paradiso 24 Dante adopts the language of reason, indeed the language of scholastic argumentation, thus compelling us to think about the dialectic between faith and logic.

By proceeding rationally and logically, he finds an extremely effective way to make us think about faith: the essence of faith is the capacity to believe without proof, without the evidence of logic or syllogistic reasoning.

Dante prepares himself to be tested by Saint Peter in the way that the baccialier prepares to be questioned by the maestro (46-48, cited above). The questions posed by Saint Peter are, first, “what is faith?” (53), and, second, “do you possess it?” (85).

The first question is put quite stirringly, requiring the pilgrim to “make himself manifest”: «Di’, buon Cristiano, fatti manifesto: / fede che è?» (Good Christian, speak, show yourself clearly: what is faith? [Par. 24.52-53]). Dante offers as his authority Saint Peter’s “dear brother” (62), Saint Paul.

The definition of faith is from Paul’s Epistle to the Hebrews, “Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” (Hebrews 11:1):

fede è sustanza di cose sperate e argomento de le non parventi; e questa pare a me sua quiditate. (Par. 24.64-66)

faith is the substance of the things we hope for and is the evidence of things not seen; and this I take to be its quiddity.

In other words, Dante has created a marvelous chiasmus between his form and his content, his signum and his res. The form or modality of discourse of Paradiso 24 is reasoned argument and syllogistic logic, the tools that lead to understanding and to intellectual “sight”. The content or matter of Paradiso 24 is faith, which consists precisely of believing without benefit of sight.

For the rationalist, “seeing is believing”. For the person of faith, belief is possible without rational proof, without seeing. Indeed, the essence of faith, defined as “the evidence of things not seen”, is believing without seeing.

A thematic of textuality and truth, a probing of what constitutes true textuality, runs through the examination canti. Broached by Paradiso 23’s redefinition of the Commedia as a “sacrato poema” (Par. 23.62), the theme is picked up by the reference in Paradiso 24 to Saint Paul as the “veracious pen” (“verace stilo” [Par. 24.61]) and continues in an investigation of the basis of the Bible’s own textual authority.

Why, comes the startling question, does the pilgrim hold the Old and New Testaments to be truly divine speech?

Io udi’ poi: «L’antica e la novella proposizion che così ti conchiude, perché l'hai tu per divina favella?» (Par. 24.97-99)

I heard: “The premises of old and new impelling your conclusion—why do you hold these to be the speech of God?”

The pilgrim’s reply is that the proof of the Bible’s truth lies in the “works that followed” (“l’opere seguite” [101]): the miraculous events that were precipitated and that act as confirmation. In other words, the proof of the Bible’s truth lies in the miracles that confirm what the biblical accounts relate. But Saint Peter continues an analysis that leaves very little to be taken on faith, pointing out the circularity of the pilgrim’s argument: the only source for the truth of the miracles is the same biblical textuality whose truth he is trying to prove.

Peter’s language is the language of Aristotelian logic:

Risposto fummi: «Di’, chi t’assicura che quell’opere fosser? Quel medesmo che vuol provarsi, non altri, il ti giura». (Par. 24.103-05)

“Say, who assures you that those works were real?” came the reply. “The very thing that needs proof—no thing else—attests these works to you.”

Saint Peter is pointing to the logical fallacy of petitio principi, where the conclusion that one is attempting to prove is included in the initial premise of the argument. As Saint Peter cogently says: you can’t use the miracles recounted in the Bible to prove the truth of the Bible when our only guarantee of the truth of those miracles is the very Bible whose truth we are trying to prove.

I find this passage incredibly moving, for in it Dante shows us why faith is a “leap” for a person constituted as he is: a man committed to reason and to following the path of reason as far as it will go, a man who is completely aware of the inherent logical frailty of all guarantees of divine truth. For such a man, faith is an achievement.

Dante resolves the syllogistic stalemate on Biblical truth by bringing in God, Whose presence in history in the form of Christianity is declared to be so great a miracle that none other is needed (106-11). But, as with Dante’s challenge to God’s injustice toward the man born on the banks of the Indus in Paradiso 19, so here, too, what counts is the frank and open airing of a problem that few would acknowledge.

When the pilgrim is asked, earlier in the canto, if he possesses faith, the language is economic, material, and quotidian. Saint Peter’s characterization of faith as “moneta” and query as to whether Dante has it “in his purse” have a homespun quality that seem very far from the ratiocinative syllogisms we associate with Paradiso 24. Drawing on the many passages in the Commedia in which the faulty minting of coins is a hallmark of civic corruption (see for instance Inferno 30 and Purgatorio 6), here Dante imagines his own faith as a coin whose alloy, weight, and stamp cannot be placed in doubt:

«Assai bene è trascorsa d’esta moneta già la lega e ’l peso; ma dimmi se tu l’hai ne la tua borsa». Ond’io: «Sì ho, sì lucida e sì tonda, che nel suo conio nulla mi s’inforsa». (Par. 24.83-87)

“Now this coin is well-examined, and now we know its alloy and its weight. But tell me: do you have it in your purse?” And I: “Indeed I do—so bright and round that nothing in its stamp leads me to doubt.”

By the end of Paradiso 24, where ratio and intellect are so valued as to put the veracity of the Bible itself into discussion, we are in a position to understand somewhat better why Dante would think of his faith as a treasured coin, “so bright and so round” and so safely nestled in his “purse”: faith is a very impressive coin indeed when it is so dearly bought.

[1] The noun silogismo appears also in Paradiso 11.2, where it is used in the plural, while the verb silogizzar is used of Sigier of Brabant in Paradiso 10.138.

Return to top

Return to top