Purgatorio 3 is one of the canti that falls into two parts: the first half is devoted to Virgilio and virtuous pagans and the latter half to the pilgrim’s encounter with Manfredi.

At the outset of Purgatorio 3, the poet redresses the correction of Virgilio at the hands of Cato that occurred at the end of the previous canto. We note how in his own voice — not as pilgrim but as Dante-poet — he goes out of the way to deconstruct the humiliation of Virgilio that he himself constructed:

i’ mi ristrinsi a la fida compagna: e come sare’ io sanza lui corso? chi m’avria tratto su per la montagna? (Purg. 3.4-6)

I drew in closer to my true companion. For how could I have run ahead without him? Who could have helped me as I climbed the mountain?

This is a beautiful example of the Dantean mastery of authorial dialectic: he first pushes the reader to feel one thing, and then he pushes the reader the other way, the better to maintain a thick and lifelike texture in which it is difficult to pinpoint what is “wrong” and what is “right”.

In a melancholy vein, Virgilio expounds on the mysteries that cannot be plumbed by human reason. If reason alone could satisfy our desire to know, he says, Dante would not have seen Aristotle and Plato condemned to a fruitless longing to know, in the place where their longing will never be fulfilled (Limbo):

«e disiar vedeste sanza frutto tai che sarebbe lor disio quetato, ch’etternalmente è dato lor per lutto: io dico d’Aristotile e di Plato e di molt’altri»; e qui chinò la fronte, e più non disse, e rimase turbato. (Purg. 3.40-45)

“You saw the fruitless longing of those men who would—if reason could—have been content, those whose desire eternally laments: I speak of Aristotle and of Plato— and many others.” Here he bent his head and said no more, remaining with his sorrow.

These opening canti of Purgatorio, from the encounter with Cato in Purgatorio 1 to Virgilio’s speech in Purgatorio 3 that culminates in the fates of Aristotle and Plato, constitute a major installment in the Commedia’s Virgilio-narrative, which is a dialectical meditation on classical culture.

These canti also constitute an ongoing meditation on the body, treated with pathos and nostalgia: the body of his friend that Dante tries to embrace in Purgatorio 2, the body of Virgilio that does not cause a shadow in Purgatorio 3 (causing Virgilio to briefly note the virtual nature of the body that Dante sees), the body of Manfredi that still bespeaks his erstwhile beauty and charm. A quasi-nostalgia for the body — our bodies are the emblems of all that we lose when we lose life on earth — is a running trope throughout Ante-Purgatory.

As noted, we are in an area called by the commentary tradition “Ante-Purgatory.” Bearing in mind the enormous carte blanche that Dante enjoys with respect to the creation of Purgatorio (discussed in the Commento on Purgatorio 1), we see that Dante has invented the concept of those who must delay their entrance into Purgatory proper (see The Undivine Comedy, p. 34). In Purgatorio 3 we encounter a first group of delayed souls: those who were excommunicated by the Church.

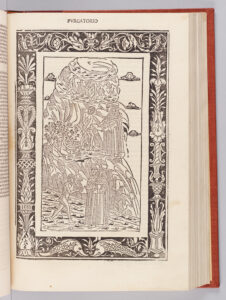

Among the excommunicates, we encounter Manfredi, the son of Emperor Frederic II. Manfredi was a great warrior and known as the epitome of chivalric virtues, a Christian version of Saladin (see Inf. 4.129). As a Florentine, and hence a Guelph, Dante was raised midst anti-imperial propaganda, and yet he shows himself receptive to the legend of Manfredi’s princely glamor, describing his wounded beauty thus:

Io mi volsi ver lui e guardail fiso: biondo era e bello e di gentile aspetto, ma l’un de’ cigli un colpo avea diviso. (Purg. 3.106-08)

I turned to look at him attentively: he was fair-haired and handsome and his aspect was noble—but one eyebrow had been cleft.

The two parts of Purgatorio 3 — the section on Virgilio and virtuous pagans at the beginning and the meeting with Manfredi in the latter half — are linked by a profound sense of pathos with respect to human vulnerability and loss: a vulnerability captured in the literal wound that mars Manfredi’s beauty.

The celebration of Manfredi’s “noble aspect” is all the more interesting given that Dante’s family fought against Manfredi and the Ghibellines, led by the exiled Florentine, Farinata (see Inferno 10) at Montaperti.

The presence of a group of saved excommunicates raises the issue of Dante’s willingness to go against church doctrine. To be excommunicated is to be excluded from the communion of Christians, and to be excluded from Christian burial. And yet Dante explicitly makes the point that an excommunicate can be saved. With respect to Manfredi, he explicitly says that the pope who excommunicated him was unable to read the face of God’s mercy (Purg. 3.124-26).

The issue of excommunication is not the only issue: Manfredi says that he repented of his terrible sins at the last moment of life, and so his story is also analogous to those of the late repentant whom we will meet in Purgatorio 5, including Bonconte da Montefeltro. There is a nexus of canti, going back to Inferno 27 and Bonconte’s father Guido da Montefeltro, which pose the following questions: What constitutes true repentance? What constitutes true conversion? In Inferno 27 we learn that not even a papal absolution can absolve one if one has not truly repented. Purgatorio 3 shows us that if you have truly repented, not even a papal excommunication can damn you.

Return to top

Return to top