The first 30 verses of Paradiso 13 are again devoted to the mystical dance of the two concentric circles of wise men. They are, like the analogous verses that open Paradiso 12, very rhetorically complex. In this instance, rather than the multi-layered comparison to a double rainbow that we find in Paradiso 12, Dante treats us to a multi-layered address to the reader.

Paradiso is no less devoted to realism than Inferno and Purgatorio. However, in the third cantica, the poet has a far harder task, not because the reality that his realism is attempting to represent is less real. If anything it is more real, for we have reached the ground of all reality. We have reached the ground of being itself.

The reality that Dante wants to represent in Paradiso is less a reality of persons, places, and things, and more a reality of being itself. In other words, the reality now being portrayed is abstract. We could call the realism of Paradiso a “conceptual realism”. By this I mean that it is a realism that is committed to the representation of reality beyond space-time.

We could think of what has happened as our having entered a physics classroom. What is taught in this classroom regards the real, but it seems less “realistic” to most students/readers. I discuss this divergence between reality and the representation of reality in my essay “Dante and Reality/Dante and Realism (Paradiso)” (cited in Coordinated Reading), where I also make an analogy between the goal of Dante in Paradiso and the goal of physicist Stephen Hawking in his book, A Brief History of Time.

In this physics classroom that we have entered, the addresses to the reader take on a different tone. Knowing well that the path ahead will offer few of those blandishments of realism that readers crave — or better: the path ahead offers few of the types of realism that readers crave —, Dante begins Paradiso 2 with the stern warning to turn back: read no further, he says, lest your ships be lost in the great watery deep, far from the comforts and safety of shore.

The multi-layered address to the reader that opens Paradiso 13 takes a different tack. To the reader who has persevered and reached the heaven of the sun, Dante now gives homework: a lesson in how to conceptualize and hold onto the reality that he is here representing.

Dante now gives the reader a task of visualization, one that is in effect a lesson in how to access this new kind of realism: conceptual or geometric realism. We could also call this a task in how to make realistic — realizable — the non-realistic. The non-realistic is of course not the same as the non-real.

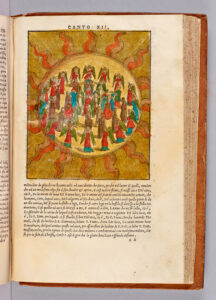

In order to visualize the twenty-four souls dancing around him, the reader must imagine stars: first fifteen stars of the first magnitude, followed by the seven stars of Ursa Major, followed by the two brightest stars of Ursa Minor, thus reaching a total of twenty-four stars. Dante orders the reader to imagine — note the thrice repeated “Imagini” — and to do the work of holding the image in the mind:

Imagini, chi bene intender cupe quel ch’i’ or vidi – e ritegna l’image, mentre ch’io dico, come ferma rupe –, quindici stelle che ’n diverse plage lo ciel avvivan di tanto sereno che soperchia de l’aere ogne compage; imagini quel carro a cu’ il seno basta del nostro cielo e notte e giorno, si ch’al volger del temo non vien meno; imagini la bocca di quel corno che si comincia in punta de lo stelo a cui la prima rota va dintorno . . . (Par. 13.1-12)

Let him imagine, who would rightly seize what I saw now—and let him while I speak retain that image like a steadfast rock— in heaven’s different parts, those fifteen stars that quicken heaven with such radiance as to undo the air’s opacities; let him imagine, too, that Wain which stays within our heaven’s bosom night and day, so that its turning never leaves our sight; let him imagine those two stars that form the mouth of that Horn which begins atop the axle round which the first wheel revolves . . .

In the above passage the reader is commanded to do the work of imagination — the work of giving plasticity and realism to what Dante saw — with three imperatives (“imagini”) and with a series of precise mental instructions for visualization. These are in effect instructions for self-entertainment, in the etymological sense of the word “entertainment”, which comes from the Latin verb tenere, “to hold”. How are we to make the twenty-four lights of the twenty-four wise souls entertaining — that is, hold-on-to-able?

Dante is teaching us how to first visualize in our minds and then how to hold onto the abstract verities that he is describing.

The reader must hold onto the first image as though to a firm rock: “e ritegna l’image, / mentre ch’io dico, come ferma rupe” (let him while I speak retain that image like a steadfast rock [Par. 13.2-3]). The poet on his side of the collaboration proceeds to unfold the second image and then the third. If the reader can hold the sequential images in her/his mind simultaneously, then s/he has an opportunity to create the composite image, which is still but a shadow of what Dante saw: “avrà quasi l’ombra de la vera / costellazione” (and he will have a shadow — as it were — of the true constellation [Par. 13.19-20]).

The haunting phrase that designates that which we obtain after engaging in the arduous work of conceptualizing the reality of Paradiso —we obtain only “l’ombra de la vera / costellazione” (the shadow of the true constellation) — sums up the necessary failure that attends our enterprise: the enterprise of the author who tries to represent this reality, and the enterprise of the reader who struggles to understand and hold onto it.

In Paradiso 13.31 Saint Thomas breaks the silence and begins to speak again, noting that one of Dante’s two dubbi is still unresolved. Thomas dealt with “u’ ben s’impingua” from Paradiso 10.96 in his explanation that the Dominicans used to fatten before they began to stray, an explanation found in the coda on the decadence of the Dominicans in Paradiso 11. He has not yet dealt with Dante’s perplexity about “non surse il secondo” from Paradiso 10.114.

The question is: How can the fifth light of the first circle — Solomon — be the wisest of men? Would not Adam and Christ be more worthy of that honor? Thomas says he will explain in such a way that Dante’s belief and Thomas’s speech will be equally true, and he says this by using the metaphor of the circle and its center: “e vedrai il tuo credere e ’l mio dire / nel vero farsi come centro in tondo” (you will see: truth centers both my speech and your belief, just like a circle’s center [Par. 13.50-51]).

The imagery here is that which governs this heaven: just as the beliefs of wise men who held such disparate philosophical views on earth now meet at the truth as at the center of a circle, so Dante’s belief and Thomas’s explanation will meet at the truth “as the center in a circle”: “come centro in tondo” (51).

As we have seen Dante do with respect to previous dubbi in Paradiso, a distinction is now introduced in order to allow two different positions to be reconciled. The distinction that Thomas will eventually introduce is that of “regal prudenza” (regal prudence [Par. 13.104]), or kingly wisdom: the wisdom that befits a king. In other words, it turns out that Thomas was not speaking of absolute wisdom when he referred in Paradiso 10 to Solomon as the wisest of men, but to a specific kind of wisdom, that which is appropriate to kings.

Dante’s intellectual procedure here is similar to that which he follows in Paradiso 4, when Beatrice introduces the distinction between absolute will and conditioned will. The use of solutio distinctiva to reconcile intellectual positions is pioneered in Paradiso 4, and we will encounter it frequently thereafter, for it turns out to be essential to the narrative mechanics of the Paradiso as a whole. See “Dante Squares the Circle: Textual and Philosophical Affinities of Monarchia and Paradiso (Solutio Distinctiva in Mon. 3.4.17 and Par. 4.94-114),” cited in Coordinated Reading.

Having made this distinction (“Con questa distinzion prendi ’l mio detto” in Par. 13.109), Thomas draws out the social implications of his practice, critiquing those fools who do not distinguish and rush to make hasty judgments. This critique includes the ancient philosophers Parmenides, Melissus, and Bryson (Par. 13.125) and the heretics Sabellius and Arius (127). With a further critique of non-philosophers who rush to judgment without having engaged in rigorous thought, the canto draws to its end.

However, in jumping to Thomas’s application of the solvent of logical distinction to the pilgrim’s dubbio about the fifth soul of the first circle, I have skipped over this canto’s molten core. In between enunciating Dante’s second dubbio and promising to answer it, and then supplying the distinction that allows him to answer it, Thomas gives voice, in Paradiso 13.52-87, to one of the great creation discourses of the third cantica. This discourse links back to the passages on creation in Paradiso 1, 2, and 7, and looks forward to the creation discourse of Paradiso 29. The creation discourse of Paradiso 13 is both theologically fundamental and extraordinarily beautiful.

Technically, Thomas brings in the issue of creation in order to let Dante know that he is in fact correct in his assumption that of all created beings Christ and Adam are the most perfect. The technical pretext allows Dante to turn to the magnificent spectacle of the one becoming many while somehow still remaining eternally one, a process caught by the poet in the rhyme words:

Ciò che non more e ciò che può morire

non è se non splendor di quella idea

che partorisce, amando, il nostro Sire;

ché quella viva luce che sì mea

dal suo lucente, che non si disuna

da lui né da l’amor ch’a lor s’intrea,

per sua bontate il suo raggiare aduna,

quasi specchiato, in nove sussistenze,

etternalmente rimanendosi una. (Par. 13.52-60)

Both that which never dies and that which dies are only the reflected light of that Idea which our Sire, with Love, begets; because the living Light that pours out so from Its bright Source that It does not disjoin from It or from the Love intrined with them, through Its own goodness gathers up Its rays within nine essences, as in a mirror, Itself eternally remaining One.

We note in the above verses the two rehearsals of the Trinity:

- “quella idea [the Son] / che partorisce, amando [the Holy Spirit], il nostro Sire [the Father]” (53-54)

- “quella viva luce [the Son] che si mea / dal suo lucente, che non si disuna / da lui [the Father] né da l’amor [the Holy Spirit] ch’a lor s’intrea” (55-57)

We note, too, the performance of the Trinity in the play of the rhyme words: “disuna” (to un-one itself), “s’intrea” (to en-three itself), “aduna” (to make one), and “una” (one).

In conclusion, let us consider ”Ciò che non more e ciò che può morire” (52), which means, literally, “That which does not die and that which can die”. In other words, Dante here references “all created beings” — that is, “all living things”.

“Ciò che non more” (“that which does not die”) embraces those created beings that are created directly by God, those beings that, in the creation discourse of Paradiso 7, are created “sanza mezzo”, without the mediation of the heavens: “Ciò che da lei sanza mezzo distilla” (Par. 7.67) and “Ciò che da essa sanza mezzo piove” (Par. 7.70). We note how the magnificent formulation of Paradiso 13 — “Cìo che non more e ciò che può morire” (52) — echoes the magnificent formulations, also beginning with “Ciò che”, from Paradiso 7. We recall from Paradiso 7 that those beings that are created without mediation, immediately by God, are gifted with immortality.

“Ciò che può morire” (“that which can die”) refers to those created beings that are not created directly by God but are created through the mediation of the heavens, that are therefore “subject to the power of the new things”: “a la virtute de le cose nove” (Paradiso 70.72). The heavens are “new”, because they are created by God, Who is instead forever not new and never sees a “new thing”: “Colui che mai non vide cosa nova” (Purg. 10.94). Those things that are created through the mediation of the heavens are things that, again in the language of Paradiso 7, will come to corruption and last but little: “venire a corruzione, e durar poco” (Par. 7.126).

If we listen to the sound and the rhythm of “Ciò che non more e ciò che può morire” — if we say the verse out loud — we hear the vibration of being and creation as presented by Dante in Paradiso 13. We hear the sound and the rhythm of the waves crashing on the shore of the great sea of being itself, as caught again in the canto’s last verse: “ché quel può surgere, e quel può cadere” (for one may rise, and one may fall [Par. 13.142]).

Return to top

Return to top