- The travelers must climb down a rockslide in order to access the first ring of the seventh circle; Virgilio calls this rocky mass “questa ruina” (this ruin [Inf. 12.32])

- The ruine of Dante’s Hell were caused by Christ’s Harrowing of Hell, Christ’s violation of Hell’s territorial integrity: they are places where the infernal infrastructure was destroyed by the earthquake that preceded the Christ’s arrival

- Thus, the ruine are a continual witness to Hell’s defeat, its impotence in the face of an all-powerful divinity

- The ruine are linked to Christ’s Harrowing of Hell, and the Harrowing of Hell is linked, in the Commedia, to Virgilio, who, in Inferno 4, introduces the Harrowing of Hell to the poem as an event that he personally witnessed

- A new installment in the Commedia’s Virgilio-narrative: discussion of the ruina serves to recall the moment in which Virgilio witnessed Christ’s Harrowing, the moment when he watched Christ liberate souls from Limbo, not including himself

- The pilgrim is substantial, endowed with a real body that causes him to move rocks with his feet; the souls’ bodies are insubstantial, as we can infer from verse 96 (describing the pilgrim): “ché non è spirto che per l’aere vada” (for he’s no spirit who can fly through air)

- The distinction between a specific action or sin and the underlying vice, a distinction previously discussed in the Commento on Inferno 6; here we must distinguish between specific violent actions such as murder and pillage, which are sins, while greed and anger — “cieca cupidigia e ira folle” (Inf. 12.49) — are the underlying vices

- Cupidigia is a “super-vice”, a composite of vices of desire, and is embodied in the lupa of Inferno 1

- In this canto Dante uses the word cupidigia for the first time in the Commedia, as also the word tirannia: in Dante’ analysis cupidigia and ira together lead to political violence, to tirannia

- The concept of tirannia refers both to ancient and modern tyrants; it is part of an ongoing political analysis of contemporary despotic forms of governance on the Italian peninsula

- Dante has a particular interest in castigating the tiranni of the Malatesta clan of Rimini, whose dynasty is featured in Inferno 5 (indirectly), Inferno 27, and Inferno 28

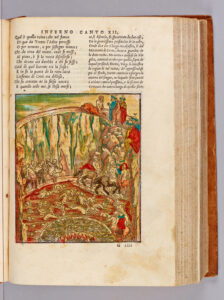

[1] Inferno 12 begins with a difficult climb down a steep and mountainous rock face. The terrain is passable, albeit tortuous, as if the travelers were making their way in the wake of an alpine landslide. On the edge of the cliff there is a monster from classical mythology which guards the pass down to the seventh circle: the Minotaur, “l’infamia di Creti” (the infamy of Crete [Inf. 12.12]). As with the previous classical guardians of Hell, Virgilio manages Dante’s safe passage, in this case by infuriating the Minotaur and taking advantage of its irate distraction to make a run for the pass.

[2] The first section of Inferno 12, through verse 45, is an important installment in the ongoing story of Virgilio and his ability to negotiate Hell: the poet lets us see both Virgilio’s limitations vis-à-vis Christianity and his correct intuitions. Here Virgilio, who recently failed to guide Dante through the gate of Dis, which was guarded by Christian devils, once more shows himself adept at handling pagan monsters and guides Dante safely past the Minotaur.

[3] Perhaps having learned from the experience of watching the angel open the gate of Dis, Virgilio taunts the Minotaur by reminding him of Theseus, “the duke of Athens” of verse 17. Theseus is, as Virgilio states, the Greek hero who was able to defeat the Minotaur on Crete: “Forse / tu credi che qui sia ’l duca d’Atene, / che sù nel mondo la morte ti porse?” (Perhaps / you think this is the Duke of Athens here, / who, in the world above, brought you your death [Inf. 12.16-18]). Similarly, in Inferno 9, the Furies are still haunted by the “assault” of Theseus on Hades (Inf. 9.54), and the angel taunts the infernal throng with the memory of Hercules, who once defeated Cerberus (Inf. 9.97-99).

[4] Theseus and Hercules are classical forerunners of Christ, early harrowers of Hell whose actions symbolize infernal defeat. As I wrote in Dante’s Poets:

Both Theseus and Hercules are flgurae Christi, heroes who descended to the underworld to rob it of its booty, and as such both are mentioned in Inferno IX: Theseus by the Furies, who still clamor for revenge (“mal non vengiammo in Teseo l’assalto” [badly did we not avenge ourselves on Theseus Inf. IX, 54]); and Hercules implicitly by the angel, who reminds the devils of Cerberus’ ill-fated attempt to withstand the hero in Inferno IX, 97-99. (Dante’s Poets, pp. 209-10)

[5] By invoking Theseus in Inferno 12, Virgilio shows how well he has learned the lesson of the celestial agent who arrived in Inferno 9.

[6] Another recall of the episode of Inferno 8-9 occurs when Virgilio discusses the nature of “questa ruina” (this ruin [Inf. 12.32]). The word ruina (plural ruine) is Dante’s generic term for the places where the infernal infrastructure has crumbled, and thus for the rockslide that the travelers are currently traversing. Virgilio take care to tell the pilgrim that this ruina was not here when he passed this way previously, “the other time” — “l’altra fïata” (Inf. 12.34) — that he made this trip through Hell. On that other occasion, he says, the boulders that they are picking their way through had not yet fallen:

Or vo’ che sappi che l’altra fïata ch’i’ discesi qua giù nel basso inferno, questa roccia non era ancor cascata. (Inf. 12.34-36)

Now I would have you know: the other time that I descended into lower Hell, this mass of boulders had not yet collapsed.

[7] Thus, in the context of the novel sighting of a ruina, of a disruption in the landscape of Hell, we find that Virgilio references the “other time” he came this way. He presumably does so in order to reassure the pilgrim that he knows what he is doing. However, any reference to Virgilio’s first trip to lower Hell only serves to cast a shadow over our beloved guide, since it reminds us that he once undertook this same journey under the aegis of a very different power from the one that sends him now. In Inferno 2 Virgilio explains to Dante-pilgrim that he was sent to Dante’s aid by ladies from heaven, particularly Beatrice. In Inferno 9 Virgilio explains to Dante-pilgrim that he had been summoned to undertake the trip into lowest Hell on a prior occasion. The agent then was Erichtho, mistress of the dark arts.

[8] Dante’s invented Virgilian backstory of Erichtho, the sorceress from Lucan’s Pharsalia who had the power to send Virgilio on a mission to lowest Hell, raises issues that problematize not only Virgilio, but also the status of Hell itself. How can Hell’s territorial integrity have been violated in such a way, and by a pagan practitioner of the dark arts? True, Erichtho did not enter Hell herself; she instead used Virgilio as her agent. But how did she have even such limited power? These questions are never explicitly acknowledged, let alone answered.

[9] The violation of Hell and of its territorial integrity brings us necessarily to the archetypal violation: Christ’s Harrowing of Hell. This event is first mentioned in the Commedia in Inferno 4, where Virgilio explains that he witnessed it. Indeed, Christ’s arrival in Limbo and His liberation of some of the souls from the first circle is a fixed reference point for Virgilio, an event that he has never forgotten — no doubt in part because he himself was not one of the liberated souls.

[10] That fixed reference point is the moment when, newly arrived in the first circle — “Io era nuovo in questo stato” (I was new-entered on this state [Inf. 4.52]) — Virgilio witnessed the arrival of an all-powerful being who is crowned in victory: “quando ci vidi venire un possente, / con segno di vittoria coronato” (when I beheld a Great Lord enter here, / crowned with the sign of victory [Inf. 4.53-54]).

[11] Now, in Inferno 12, Virgilio correctly intuits what has happened in the time elapsed between his first journey to lower Hell, at the behest of Erichtho, and his current mission, at the behest of Beatrice. He is able to explain the cause of “questa ruina” (32): the infernal infrastructure crumbled as a result of the earthquake that preceded the Harrowing of Hell. He tells the pilgrim that the earth shook “just before” (“poco pria” [37]) the arrival of “the One who took / from Dis the highest circle’s splendid spoils”: “colui che la gran preda / levò a Dite del cerchio superno” (Inf. 12.38-39).

[12] The periphrasis that Virgilio uses for Christ, calling Him the One who robbed Lucifer of his prey, sets the militaristic tone: this passage is devoted to Christ’s conquest of Hell. The marks of Hell’s ignominious defeat remain visible in stone, in the ruine, which function as reminders of Hell’s true impotence.

[13] The Harrowing interrupts the eternity of Hell and also leaves markers of destruction on the landscape, signposts that forever recall the power of the one who opened Hell’s gate at will. By suturing his fictive Virgilio to the Harrowing of Hell, as he does immediately in Inferno 4 and then throughout Inferno in the episodes of the ruine, Dante finds a structural way to keep raising the issue of the limitations of his beloved guide.

[14] Here Virgilio is able to compensate by applying the lessons of his failure with the devils at the gate of Dis, but that failure is by no means forgotten. Indeed, the pilgrim will remind his guide of that failure again in Inferno 14, where he greets him as “Master, you who can defeat / all things except for those tenacious demons / who tried to block us at the entryway”: “Maestro, tu che vinci / tutte le cose, fuor che ’ demon duri / ch’a l’intrar de la porta incontra uscinci” (Inf. 13.43-45).

[15] Virgilio concludes discussion of “questa ruina” by explaining the earthquake that caused it in terms of the Empedoclean doctrine whereby order depends on the discord of the elements, and chaos would result from their concord. At the moment of the quake, Virgilio says, he believed that the universe “felt love”: “’i’ pensai che l’universo / sentisse amor” (I thought the universe / felt love [Inf. 12.41-42]). Although Virgilio is technically wrong in ascribing the earth’s tremor to the concord of the elements, in saying that the universe “felt love” he has in fact intuited the correct cause of the quake: the universe felt love in that it felt the arrival of Christ. Again, we see Dante dramatizing the pathos of Virgilio, the good learner, who, despite his limitations, always does his best to provide knowledge and guidance to his pupil.

* * *

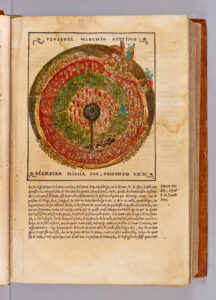

[16] Beginning in Inferno 12.46, the travelers see what lies before them in the first ring of the circle of violence. As explained in Inferno 11, the first ring of the seventh circle is devoted to punishing those who committed violence against their neighbor, in the neighbor’s person and in her/his possessions. The poet tells us of a river of blood, Phlegethon, in which are immersed and boiled the sinners who “did harm to others through violence”: “qual che per violenza in altrui noccia” (Inf. 12.48). The degree of the shades’ immersion in the boiling blood is determined by the degree of violence that they committed.

[17] The narrator interrupts his account with an impassioned apostrophe that begins “Oh cieca cupidigia e ira folle” (O blind cupidity and insane anger [Inf. 12.49]). The phrase “ira folle” in Dante’s apostrophe echoes and anticipates a series of references to anger that accrue in Inferno 12, a canto that contains four uses of the word ira, more than any other canto in the poem.

[18] Through characterizations of the Minotaur (to whom Dante also applies the verb infuriare, in verse 27), and of the centaur Pholus, as well as in his apostrophe, Dante communicates the key role of anger in the production of acts of violence: “sì come quei cui l’ira dentro fiacca” (like one whom rage devastates within [Inf. 12.15]), “ira bestial” (bestial rage [Inf. 12. 33]), “ira folle” (insane anger [Inf. 12.49]), “Folo, che fu sì pien d’ira” (Pholus, who was so full of rage [Inf. 12.72]). The trend of these expressions, especially of “ira bestial” in verse 33, is to remind us of the label given to the sin of violence in Inferno 11, where it is “la matta / bestialitade” (mad bestiality [Inf. 11.82])

[19] The textual emphasis on ira also raises the distinction between a specific action or sin and the underlying vice, a distinction previously discussed in the Commento on Inferno 6. We now have another opportunity that allows us to continue to clarify the confusing overlap that sometimes occurs between the label for a given vice and the label for a given sin. We remember that Dante’s infernal circle of lust punishes not the vice of lust but specific sinful acts caused by lust. Similarly, his infernal circle of anger punishes not the vice of anger but specific sinful acts caused by anger.

[20] In the apostrophe of Inferno 12, on the other hand, “ira folle” refers to the underlying impulse toward anger, the impulse that contributes to and nourishes the sinful acts of violence that these souls have committed. Anger is thus one of the vices that, as Dante claims in this apostrophe, “spurs” the soul to sinful action:

Oh cieca cupidigia e ira folle, che sì ci sproni ne la vita corta, e ne l’etterna poi sì mal c’immolle! (Inf. 12.49-51)

O blind cupidity and insane anger, which goad us on so much in our short life, then steep us in such grief eternally!

[21] In his apostrophe, Dante-narrator addresses cupidity and anger, describing them as internal impulses that goad the soul; he uses the verb spronare, suggesting that we are spurred by cupidity and anger in the same way that spurs goad a horse. This is an image that Dante first encountered in the context of love poetry and that he subsequently grafted into the Aristotelian ethics of the Convivio (see “Dante and Wealth, Between Aristotle and Cortesia”, in Coordinated Reading). According to the language of the above apostrophe, humans are unable to withstand the vicious spurs that goad us during our brief lives on earth (“ne la vita corta”), and are thus driven to the violent actions that then cause them to spend eternal life immersed in a river of blood.

[22] Here Dante lays bare the distinction between sin and vice and encourages the reader to think of the vices that underlie specific sins, as in Inferno 6 the narrator encouraged the reader to think of the vices that inflamed the Florentines to factional hatred and division. The sins punished in Dante’s Hell are the precise actions that the sinner committed in historical time. In this particular sub-circle of Hell, therefore, they are acts of murder, robbery, and so forth.

[23] But vice is always the underlying goad that provokes our sins. That internal goad can be anger, it can be greed — it can be any one or combination of the seven capital vices. Indeed, the vices often work together, for the underlying vices that spur an individual soul to sin are various and complex. Thus, in Inferno 6 we learn that pride, envy, and avarice are the vices that inflame Florentine hearts: “superbia, invidia e avarizia sono / le tre faville c’hanno i cuori accesi” (Three sparks that set on fire every heart /are envy, pride, and avariciousness [Inf. 6.74-5]).

[24] In the apostrophe of verses 49-51 cited above, the poet offers not only “mad anger” as a vice that spurs to violence, but also, in first place, “blind cupidity”: “cieca cupidigia e ira folle” (Inf. 12.49]). With the term cupidigia the poet gives us the opportunity to consider a “super-vice”: in Dante’s mind, cupidigia is a profoundly rapacious and greedy and narcissistic form of inordinate and immoderate desire. We remember that the most fearsome obstacle to the pilgrim’s aborted ascent up the mountain bathed in divine light in Inferno 1 is the lupa, the skeletal she-wolf who is laden with all human cravings and desires and is the cause of much human misery:

Ed una lupa, che di tutte brame sembiava carca ne la sua magrezza, e molte genti fé già viver grame (Inf. 1.49-51)

And then a she-wolf showed herself; she seemed to carry every craving in her leanness; she had already brought despair to many.

[25] As Virgilio will explain to the pilgrim, the lupa allows no one to pass, creating an impasse that leads to death, for her nature is one of never-sated desire and hunger that never ends: “mai non empie la bramosa voglia, / e dopo ’l pasto ha più fame che pria” (she can never sate her greedy will; / when she has fed, she’s hungrier than ever [Inf. 1.98-99]).

[26] Recalling that the Bible defines cupidity as “the root of all evil” — “radix enim omnium malorum est cupiditas” (1 Timothy 6:10) —, I submit that cupidigia is at the heart of Dante’s analysis of human sin. In Inferno 12, Dante uses the important word cupidigia for the first time (he will use it only five times in the Commedia: once in Inferno, once in Purgatorio, and three times in Paradiso). Cupiditas blinds us, and thus, in Dante’s final employment of the term cupidigia, in Paradiso 30, he circles back to Inferno 12 and to his early coupling of cupidigia with the adjective cieca, writing of “La cieca cupidigia che v’ammalia” (the blind greediness that bewitches us [Par. 30.139]). The “cieca cupidigia” of Paradiso 30.39 reprises the “cieca cupidigia” of Inferno 12.49 and constitutes Dante’s final comment on a vicious impulse that he examines from the beginning of the Commedia to its end.

[27] I argue that Dante understands cupidity/cupidigia as a composite of lust, gluttony, and avarice, effectively conflated into a composite super-vice.[1] In other words, cupidigia embraces all forms of excessive and aggravated desire. These are the vices treated in the top three terraces of Dante’s Mount Purgatory, the terraces whose sins are represented by the siren of Purgatorio 19. Indeed, the siren’s capacities to bewitch and to blind are recalled in Paradiso 30.139, where Dante declares that blind cupidity bewitches us, using the verb ammaliare with its connotations of seduction and enchantment: “La cieca cupidigia che v’ammalia” (Par. 30.139).

[28] In Purgatorio 19 Virgilio explains that the siren of the pilgrim’s dream represents the sins being purged on the three upper terraces of Mount Purgatory, and he is clear about the metaphorical reach of these vices; for instance, he makes explicit in Purgatorio 19 that he has extended the vice of avarice beyond excessive desire for wealth to include unbridled lust for power, honor, and glory. Most important, the vice of avarice ushers in the return of the lupa of Inferno 1, in an apostrophe at the beginning of Purgatorio 20 where once again the lupa is characterized by never-ending hunger:

Maladetta sie tu, antica lupa, che più di tutte l’altre bestie hai preda per la tua fame sanza fine cupa! (Purg. 20.10-12)

Now I would have you know: the other time May you be damned, o ancient wolf, whose power can claim more prey than all the other beasts — your hungering is deep and never-ending!

* * *

[29] The theme of classical antiquity continues. The travelers meet a group of Centaurs, creatures from classical mythology known for their violent tempers, but also for their better traits: the leader of the troop is the Centaur Chiron (Inf. 12.71), famed in antiquity as the tutor of Achilles. Chiron greets the travelers. He has realized that Dante is alive, because he sees that Dante’s feet move the rocks that he touches as he picks his way down the landslide to the plain. His feet, notes Chiron, are unlike the feet of the dead:

Siete voi accorti che quel di retro move ciò ch’el tocca? Così non soglion far li piè d’i morti. (Inf. 12.80-82)

Have you noticed how he who walks behind moves what he touches? Dead soles are not accustomed to do that.

[30] Since he is alive, Dante’s feet are substantial (in the etymological sense of the word) and able, as he descends to the first ring of the seventh circle, to move rocks. Given that he possesses substantial and rock-moving feet, Dante is unable to fly through the air as do the shades, in their virtual bodies; this is a point that Virgilio will make in the verses cited below. Because he cannot fly, Dante will need to be carried over the boiling blood when they are ready to leave this ring for the next. Consequently, Virgilio asks Chiron for an escort who will lead them to a ford and who will transport the living traveler over the river:

danne un de’ tuoi, a cui noi siamo a provo, e che ne mostri là dove si guada e che porti costui in su la groppa, ché non è spirto che per l’aere vada. (Inf. 12.93-96)

give us one of your band, to serve as companion; and let him show us where to ford the ditch, and let him bear this man upon his back, for he’s no spirit who can fly through air.

[31] Chiron delegates the centaur Nessus to guide the travelers to the ford and to carry the pilgrim over the river. This is the first occasion in which one of the infernal guardians is assigned to serve as a local guide and assistant for the travelers.

[32] This passage constitutes an important installment with respect to the nature of the virtual bodies that Dante-poet has designed for his afterlife. From verse 96, “ché non è spirto che per l’aere vada” — “for he’s no spirit who can fly through air” — we infer that the dead are able to move through air. We have already learned, in Inferno 6, that the virtual bodies of the dead are insubstantial, “empty images that seem like persons”: “lor vanità che par persona” (Inf. 6.36). The description of Inferno 6 accords well with the information offered here regarding the ability of dead souls to navigate through the medium of air: “per l’aere” (Inf. 12.96).

[33] Later in Hell the pilgrim will encounter a sinner whose body is described as though substantial: Dante pulls on the hair of the traitor Bocca degli Abati in Inferno 33. But in this instance Dante is functioning as a deliverer of infernal torment, and his ability to “touch” Bocca must be categorized as analogous to the ability of the devils to throw the barrator Ciampolo back into the pitch or to wound the schismatics.

[34] In sum, Dante’s body is substantial: it moves rocks in Inferno 12 and causes Charon’s boat to sink in Inferno 3. The souls in contrast are insubstantial: thus when Dante tries to embrace his friend Casella in Purgatorio 2, Casella’s body is an insubstantial image that cannot be embraced. The souls only appear substantial in the context of infernal (and purgatorial) torment.

[35] Virgilio also offers the centaur Chiron a concise and important description of the journey and of its principal protagonists: they are himself, Beatrice, and Dante. He was appointed the task of guiding the pilgrim, he explains, on a journey that is no pleasure trip: “mostrar li mi convien la valle buia / necessità ’l ci ’nduce, e non diletto” (it falls to me to show him the dark valley. / Necessity has brought him here, not pleasure [Inf. 12.85-86]). Their journey was induced by necessity, and Virgilio is performing an “officio” that was commissioned by Beatrice, described as one who departed from “singing alleluia” in order to give him his novel assignment: “Tal si partì da cantare alleluia / che mi commise quest’ officio novo” (For she who gave me this new task was one / who had just come from singing halleluiah [Inf. 12.88-89]). Beatrice is here aligned, through the use of the pronoun “Tal” (such a one), with the celestial agent who opens the gate of Dis. As we saw in Inferno 8 and Inferno 9, the same pronoun is repeatedly used by Virgilio to predict the arrival of the mysterious agent of deliverance.

[36] Chiron tasks Nessus with guiding the travelers to a place where the river narrows and with carrying Dante across bloody Phlegethon. Having executed this function, at the end of Inferno 12, Nessus immediately goes back over the ford; his return is communicated in Inferno 12’s last verse. At the beginning of Inferno 13 the narrator uses Nessus’ retreating haunches in order to indicate the alacrity with which the travelers turn toward the wood in front of them, the wood that marks the beginning of the second ring of the seventh circle: “Non era ancor di là Nesso arrivato, / quando noi ci mettemmo per un bosco” (Nessus had not yet reached the other bank / when we began to make our way across a wood [Inf. 13.1-2]).

* * *

[37] As the travelers proceed along the shore of Phlegethon heading for the place to ford the river, they learn that the violent souls are immersed in the boiling blood in a graduated fashion, according to the gravity of their sins. We recall that the sinners boiled in Phlegethon include both the violent against others in their persons and the violent against others in their possessions. The gravest sinners in this ring are the tyrants (“tiranni” in verse 104), despotic rulers who committed violence against their subjects both in their persons (by killing them) and in their possessions (by plundering their goods). The tiranni are therefore indicted on both counts and are immersed in blood up to their brows (Inf. 12.103-4). They both murdered and plundered, and hence are the worst offenders in the category of violence against others: “«E’ son tiranni / che dier nel sangue e ne l’aver di piglio” (These are the tyrants / who plunged their hands in blood and plundering [Inf. 12.104-5]).

[38] In his late political treatise Monarchia Dante makes a synthetic but telling comment about the nature of tyrants, a type of ruler that he had previously featured in Inferno 12, Inferno 27, Inferno 28, and Purgatorio 6 using the terms tiranno /tiranni/tirannia. In Monarchia 3.4.10, Dante defines tyrants as rulers who do not observe “publica iura” (public laws). Rather, they are pitted against the common welfare (“comunem utilitatem”) and seek only private gain (“ad propriam”):

si vero industria, non aliter cum sic errantibus est agendum, quam cum tyrampnis, qui publica iura non ad comunem utilitatem secuntur, sed ad propriam retorquere conantur. (Mon. 3.4.10)

but if such things are done deliberately, those who make this mistake should be treated no differently from tyrants who do not observe public rights for the common welfare, but seek to turn them to their own advantage.

[39] In Inferno 12, where Dante uses the terms tiranni and tirannia in the Commedia for the first time (tiranni appears twice in Book 4 of Convivio, in 4.6.20 and 4.27.14), he presents tyrants from classical antiquity as well as from contemporary Italy. Immersed in the river Phlegethon in the first ring of the circle of violence are the classical tyrants Alexander and Dionysius (verse 107) and also contemporary tyrants: the “Azzolino” of verse 110 is Ezzelino III da Romano, lord of the Marca Trevigiana (died 1259), while “Opizzo da Esti” in verse 111 is Obizzo II d’Este, lord of Ferrara (died 1293). The ravages of Ezzelino da Romano on the Marca Trevigiana are reprised in Paradiso 9, where his sister Cunizza da Romano identifies herself as coming from that hill whence descended a firebrand that destroyed the surrounding country: “là onde scese già una facella / che fece a la contrada un grande assalto” (from which a firebrand descended, / and it brought much injury to all the land about [Par. 9.29-30]).

[40] Nessus uses the noun “tiranni” in Inferno 12.104 to indicate the specific tyrants in Phlegethon, as we saw, and then he underscores the concept by using the noun “tirannia” in verse 132, where he stipulates that the deepest part of the river is reserved for this despotic form of governance: “ove la tirannia convien che gema” (where tyranny must make lament).

[41] Thus, Inferno 12 initiates an ongoing Dantean political analysis of a form of governance then emerging in Italy: lordship, despotic rule concentrated in the hands of one lord and his family. As I wrote in my essay “Only Historicize”: “Dante’s meditation on tirannia may be gleaned even from a glance at his use of the words tirannia and tiranno/tiranni in the Commedia”.[2] With respect to Inferno 12, specifically, it is also important to note that cupidigia and tirannia both appear for the first time in this canto: in Dante’s analysis, cupidigia and ira together lead to political violence, to tirannia.

[42] For Dante the concept that he calls tirannia is a key element of his assessment of the political ills that plague the Italian peninsula. Dante uses the term tirannia again in Inferno 27, in order to describe the form of governance that has taken shape in the city-states of Romagna. Queried about the condition of life in Romagna, the pilgrim replies with a resume of all the nascent despotisms that have taken root throughout the region. Only Cesena has not succumbed completely: it hovers still “between tyranny and freedom” (“tra tirannia si vive e stato franco” [Inf. 27.54]).

[43] In his book Italy in the Age of Dante and Petrarch (1216–1380), historian John Larner describes the steps by which the medieval communes fell into the hands of despots. Eventually the rule of the despot (tiranno) was legalized, with the result that the tirannie became signorie (see especially Chapter 7, “Party-leaders and signori”). In other words, as Larner cogently describes, the later signorie of the Renaissance are really legalized tirannie. Given that “the formalization of lordship in the legal institutions of the towns” occurred in Romagna mainly after Dante’s death (see Larner, p. 139), Dante was on sound footing in considering the towns of Romagna to be tirannie rather than signorie.

[44] It is worth noting that the canto in which Dante returns to the question of contemporary tirannia, Inferno 27, begins with the drawn-out simile of the “Sicilian bull”: the gruesome instrument of torture devised for his victims by the classical tyrant Phalaris of Sicily, who, interestingly, is cited by Aristotle as an example of bestiality in Nicomachean Ethics 7.5. We remember that the Minotaur flaunts a rage that is bestial, “ira bestial” (bestial rage [Inf. 12.33]), thus further underscoring a connection between Inferno 12 and Inferno 27. The coordination, in Inferno 27, of the ancient tyrant Phalaris with the contemporary tyrants of Romagna recalls the careful pairing of classical and contemporary tiranni in Phlegethon in Inferno 12. All the tiranni whom Dante names in Inferno 27 are worthy candidates for immersion in Phlegethon.

[45] In Inferno 27, Dante moves from the classical tyrant Phalaris to a roll-call of the contemporary tiranni of the Romagna region. Canto 27’s resume of despots mentions both the Polenta family of Ravenna and the Malatesta family of Rimini. These are the families into which Francesca da Polenta of Inferno 5 (now better known as Francesca da Rimini) was born, and into which she married, becoming the wife of Gianciotto Malatesta.[3] Special attention is given to the Malatesta dynasty in Inferno 27’s catalogue of Romagnol tyrants. Malatesta da Verucchio and his eldest son Malatestino, the first and second lords of Rimini, are mastiffs who “make an auger of their teeth” (48). In other words, they use their teeth to pierce their subjects’ flesh as a tool with a screw point might bore through wood:

E ’l mastin vecchio e ’l nuovo da Verrucchio, che fecer di Montagna il mal governo, là dove soglion fan d’i denti succhio. (Inf. 27.46-48)

Both mastiffs of Verrucchio, old and new, who dealt so badly with Montagna, use thier teeth to bore where they have always gnawed.

[46] The Malatesta family is one of a group of castigated tiranni in Inferno 27, whereas in the next canto Dante isolates the clan, describing one of Malatestino’s political murders achieved through the typical Romagnol method: betrayal. Malatestino became lord of Rimini after the death of his father, Malatesta da Verucchio, the founder of Malatesta despotic rule in Rimini. In Inferno 28, Malatestino is called a “tiranno fello” or “foul tyrant” (Inf. 28.81), an indictment that Dante backs up by reference to a particularly heinous crime. Malatestino is guilty of having treacherously invited to parley the two noblest citizens of Fano and then having them foully tortured and murdered:

gittati saran fuor di lor vasello e mazzerati presso a la Cattolica per tradimento d’un tiranno fello. (Inf. 28.79-81)

they will be cast out of their ship and drowned, weighed down with stones, near La Cattolica, because of a foul tyrant’s treachery.

[47] The two noblest citizens of Fano were Guido del Cassero and Angiolello da Carignana, who were “mazzerati” (Inf. 28.80): tied in a sack, thrown overboard, and drowned. For mazzerare, see the discussion of the Commedia’s contemporary forms of torture in the Commento on Inferno 27.

[48] The travelers see many shades in the river: the souls of murderers and violent brigands as well as tyrants. There is no encounter between the pilgrim and these souls, who are merely named by Nessus and viewed by the travelers. After pointing to perhaps history’s quintessential and most infamous tyrant, Attila (ruler of the Huns from 434 CE until his death in March 453 CE), called here with the traditional label “scourge of the earth” (“flagello in terra” [Inf. 12.134]), Nessus concludes his resume with the two contemporary highway robbers Rinier da Corneto and Rinier Pazzo (Inf. 12.137). He then turns away from the travelers and, in the canto’s last verse, goes back across the ford: “Poi si rivolse e ripassossi ’l guazzo” (Then he turned round and crossed the ford again [Inf. 12.139]).

[1] For this reading of the top three terraces of Mount Purgatory, see The Undivine Comedy, chapter 5, “Purgatory as Paradigm” (especially pp. 105-6); see too the Commento Baroliniano’s commentaries on the appropriate canti of Purgatorio.

[2] “Only Historicize: History, Material Culture (Food, Clothes, Books), and the Future of Dante Studies”, p. 17, cited in Coordinated Reading. On Dante’s meditation on tirannia, see Nassime Chida, “Guido da Montefeltro and the Tyrants of Romagna in Inferno 27”, cited in Coordinated Reading.

[3] I discuss the connection of Inferno 5 to Inferno 27 in my essay “Dante and Francesca da Rimini: Realpolitik, Romance, Gender”; see Coordinated Reading.

Return to top

Return to top