In Paradiso 30 the pilgrim experiences visions that transition from a river banked with springtime flora to a verdant amphitheater to a redolent rose to a celestial Jerusalem: the poet’s representational phantasmagoria slide from one image to another in a classic example of the high Paradiso’s jumping discourse. And yet, as cued by the political theme that provides Beatrice her last speech, Paradiso 30 as a whole displays a mixed mode, in which the language of difference coexists with the language of mystical unity.

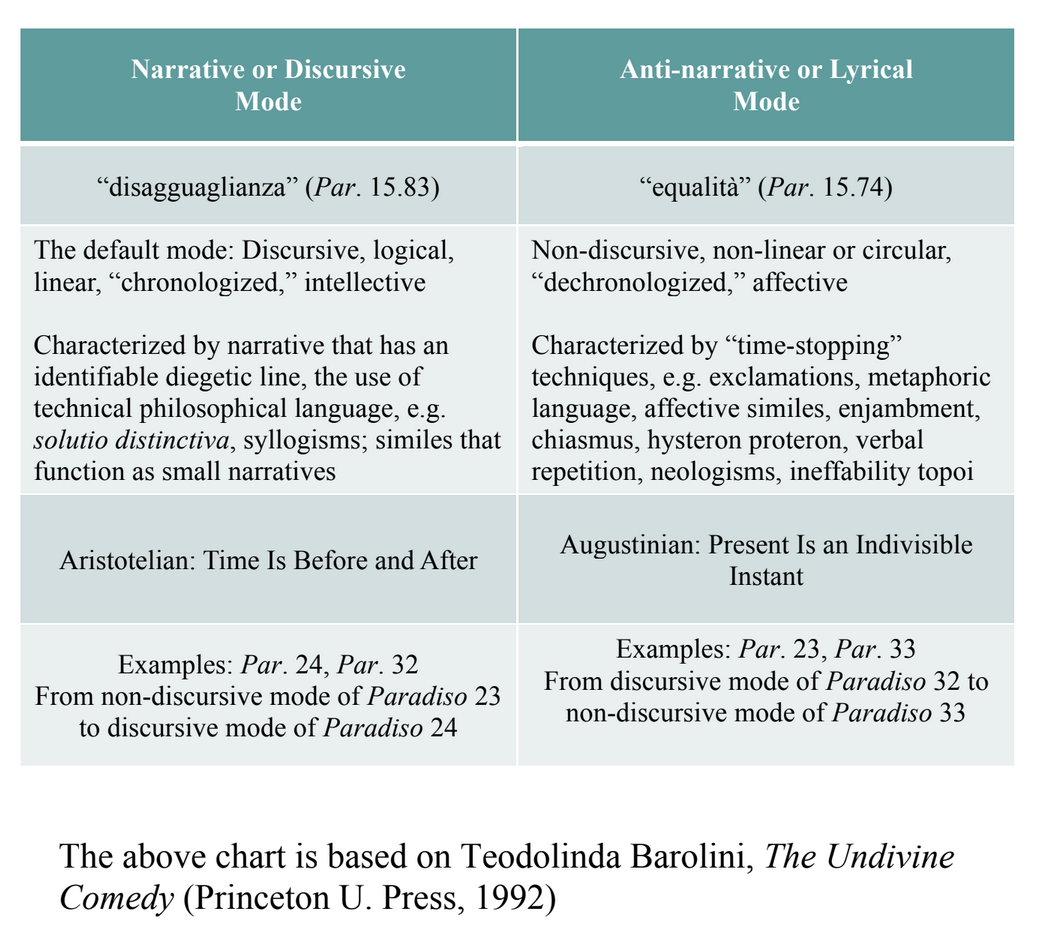

In The Undivine Comedy, I write about the Paradiso’s two textual modes: one (the backbone of the Commedia) is discursive, logical, linear, intellective, governed by difference and distinction; the other is “lyrical”, anti-narrative, non-discursive, non-linear, affective, metaphoric, chiasmic, enjambed, governed by the (ultimately impossible) attempt to thwart difference and to create the linguistic effect of unity. Here is a chart outlining the two modes:

In Chapter 7 of The Undivine Comedy, “Nonfalse Errors and the True Dreams of the Evangelist,” I show, à propos the dreams of Purgatorio, how the percentage of the lyrical style begins to increase within the overall texture of the poem as it proceeds (pp. 163-65). The three chapters devoted to Paradiso spell out the rising admixture of the lyrical mode — what in the last chapter of The Undivine Comedy I describe as the jumping or enjambed mode, the mode that creates circulata melodia — within the third cantica.

Paradiso 23 is probably the Paradiso’s most purely affective and lyrical canto. Paradiso 23 is a circulata melodia, to adopt the language of the canto itself. In the Commento to Paradiso 23 you will find a discussion of how Dante works to fracture the narrative line of that canto and to “circularize” his language. But not even Paradiso 23 belongs completely to one mode.

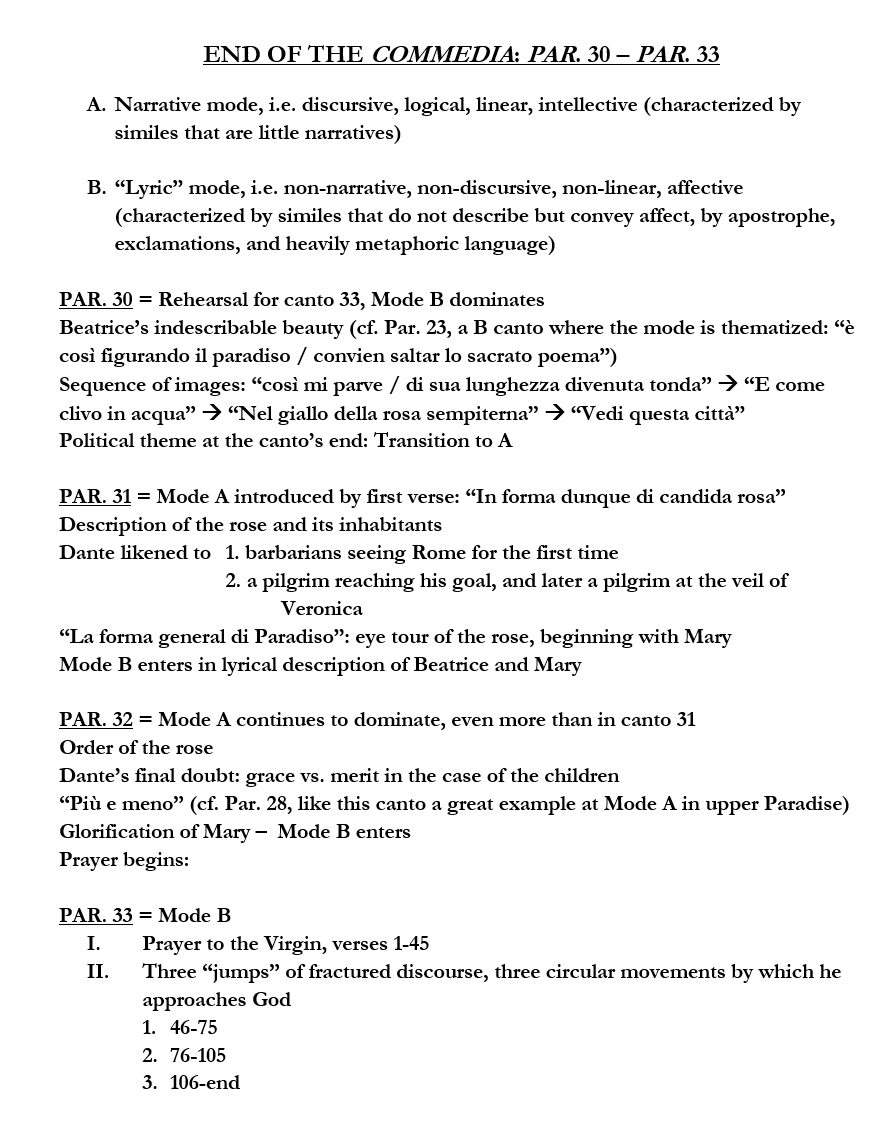

Here is a diagram of Paradiso 30-33 that parses the final four canti in terms of their oscillations between the two textual modes outlined in the chart above. You will also find, at the end of this essay, the same diagram in its original form as an old class handout, one that considerably predates The Undivine Comedy.

As the diagram shows, Paradiso 30 is to a great degree written in the lyrical style: it is dense with metaphoric language — the pilgrim drinks with his eyes from the river of light, the rose is redolent with the perfume of praise — although it veers away from lyricism at the end. Paradiso 31 and 32, while having lyrical moments (canto 32 has fewer such than canto 31), constitute instead a final attempt to bring order and discursivity to the representation of Paradise.

A final point in this preamble regards narrative structure. Looking back over the titles of the commentaries on the canti of Paradiso, you will see that the title of Paradiso 21 is “The Beginning of the End”. For reasons that I discuss in the Commento on Paradiso 21, I place the beginning of the end of the Commedia in the heaven of Saturn, the seventh heaven. Structurally, the beginning of the end includes the great narrative block of the eighth heaven, the heaven of the fixed stars: this heaven commences toward the end of Paradiso 22 and concludes about two-thirds of the way through Paradiso 27, and it is book-ended by the two Orphic moments of looking back at earth. What better way to signal the beginning of the end of this journey than to look back over its entire length?

In the canti devoted to the heaven of the fixed stars, as elsewhere, there is a principle of narrative variatio at work: linguistic unity, very hard to sustain, is always a poetic explosion (as in Paradiso 23) that is preceded and followed by a return to discursivity and difference.

We can apply these same categories to the last six canti of the Paradiso. With regard to the formal disposition of Paradiso’s final six canti, we have hitherto noted a 2 + 4 arrangement: two canti constituting, geographically, the Primum Mobile (Paradiso 28-29); and four canti constituting, geographically, the Empyrean (Paradiso 30-33).

From the point of view of alternations in narrative mode, however, we can view the same six canti as forming a 3 + 3 arrangement: two canti in the discursive mode (Paradiso 28-29), followed by one anti-narrative canto (Paradiso 30); and again, two canti in the discursive mode (Paradiso 31-32), followed by a final lyrical explosion (Paradiso 33).

With respect to both sets of three canti (set 1=Paradiso 28-30 and set 2=Paradiso 31-33), each set creates a crescendo: a movement from the logical/discursive mode to a lyrical peak. The logical/discursive/intellective canti prepare for the explosions of unity that follow. And this unity can best be achieved — in the non-unified medium of language — negatively: by not doing what has just been done, by rejecting the discourse that is privileged in the canti of difference.

In other words, Paradiso 28-29 enable Paradiso 30 to be forged as the antithesis of themselves, and likewise, Paradiso 31-32 prepare for the poem’s finale. The pattern in the two sets is basically the same, with the proviso that while Paradiso 28-29 move from more difference in canto 28 to less in canto 29, Paradiso 31-32 move from less difference in canto 31 to more in canto 32, the better to offset canto 33.

***

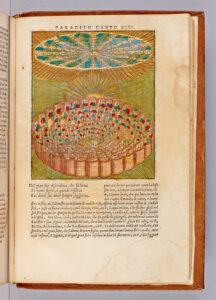

The intellective stamp of Paradiso 31 is evident from its opening verse, from the strong metrical beat that falls on the verse’s centerpiece, the intellectualizing “dunque” that mediates between “In forma” on the one hand and “di candida rosa” on the other. A word that has over the centuries been earmarked for use by teachers and scholars, the sublime dunque of Paradiso 31.1 hastens the passage from Paradiso 30’s lyrical rose redolent of praise to the more prosaic rose of Paradiso 31 and 32: a categorized and hierarchical rose, whose form is to be explained, unfolded, shorn of all mystery.

“In forma dunque di candida rosa” (So, in the shape of that white rose” [Par. 31.1]) declares the narrator, at the same time announcing the explanatory and didactic functions of these canti, whose duty is to explore the shape and content of paradise. These canti encompass the “general form of Paradise” — the “forma general di paradiso” as it will later be called (Par. 31.52) — in the language of formal exposition.

As compared to Paradiso 33’s metaphoric vision of the universe bound by love in one volume, a vision wherein the poet thinks he saw, because he still feels, the universal form of all things, in Paradiso 31 and 32 the poet’s task is not to feel the form of things so much as to explain, describe, and, as much as possible, divulge. In these canti, and especially in Paradiso 32, his task is to reason why: not to try to communicate a private and trans-rational emotion but to sustain a rational, discursive, and public inquest into the forma general di paradiso.

In the same way that the transition from Paradiso 23 (mystical, visionary, lyrical) to Paradiso 24 (discursive, analytical, intellective, narrativized) finds its emblem in the transition from the lush affective similes of canto 23 to the narrative simile of the bachelor student in canto 24, so the lush metaphors of Paradiso 30 give way, in Paradiso 31, to the narrativized simile of the barbarians who come to Rome. In this simile that reads like a brief narrative, the barbarians are amazed at the Lateran and the other monuments of the imperial city:

Se i barbari, venendo da tal plaga che ciascun giorno d’Elice si cuopra, rotante col suo figlio ond’ella è vaga, veggendo Roma e l’ardua sua opra, stupefaciensi, quando Laterano a le cose mortali andò di sopra (Par. 31.31-36)

If the Barbarians, when they came from a region that is covered every day by Helice, who wheels with her loved son, were, seeing Rome and her vast works, struck dumb (when, of all mortal things, the Lateran was the most eminent) . . .

The amazement of the barbarians who see the Lateran and the wonders of Rome is used to express the amazement of the pilgrim who sees the rose of the Empyrean in all its glory. The barbarians give way to this breathtaking description of the pilgrim’s amazement at his experience:

io, che al divino da l’umano, a l’etterno dal tempo era venuto, e di Fiorenza in popol giusto e sano di che stupor dovea esser compiuto! (Par. 31.37-40)

then what amazement must have filled me when I to the divine came from the human, to eternity from time, and to a people just and sane, from Florence came!

Three transitions render the pilgrim’s experience of Paradise, each one more effective than the previous: he has come (1) to the divine from the human, (2) to eternity from time, and — reversing directionality, and importing the proper name “Fiorenza” (similarly the proper name “Laterano” in the comparison to the barbarians) into the string of abstract nouns (“divino”, “umano”, “etterno”, “tempo”), we arrive at the stunningly localized third transition — (3) from Florence to a people who are just and sane.

The boldness of Dante’s incarnational and historicized poetics is distilled in the words “di Fiorenza in popol giusto e sano”: how brave a poet must be to put “Fiorenza” — to put, in effect, his self — into verses that are otherwise made of words like “divino”, “umoano”, “etterno”, and “tempo”.

Dante-pilgrim, like (in another travel simile, reminiscent of the barbarians reaching Rome) a pilgrim who has arrived at the temple that he had vowed to reach, now participates in a visual tour of the rose, “passeggiando” — strolling! — with his eyes through the living light:

E quasi peregrin che si ricrea nel tempio del suo voto riguardando, e spera già ridir com’ello stea, su per la viva luce passeggiando, menava io li occhi per li gradi, mo sù, mo giù e mo recirculando. (Par. 31.43-48)

And as a pilgrim, in the temple he had vowed to reach, renews himself—he looks and hopes he can describe what it was like— so did I journey through the living light, guiding my eyes, from rank to rank, along a path now up, now down, now circling round.

While Dante is taking in “the general form of paradise” (“La forma general di paradiso” [Par. 31.52]), he is surprised by the unexpected change of his guide. He turns to share his experience with Beatrice. In the same way, on a similar occasion in Purgatorio 30, he turns to share his experience with Virgilio. And, in the same way that Virgilio disappeared upon the arrival of Beatrice, now too a substitution has occurred.

Where he had expected to see “the one”, now instead he sees “another”: “Uno intendea, e altro mi rispuose” (Where I expected one, another answered [58]). The altro of verse 58 is an old man, Saint Bernard:

Uno intendea, e altro mi rispuose: credea veder Beatrice e vidi un sene vestito con le genti gloriose. (Par. 31.58-60)

Where I expected her, another answered: I thought I should see Beatrice, and saw an elder dressed like those who are in glory.

St. Bernard of Clairvaux, a noted twelfth-century Cistercian mystic, points to Beatrice in her celestial throne (69) and — after the pilgrim speaks a farewell prayer of thanks to his beloved — he invites Dante to complete his quest by continuing his “eye tour” of the rose, “flying with your eyes through this garden” (verse 97):

E ’l santo sene: «Acciò che tu assommi perfettamente», disse, «il tuo cammino, a che priego e amor santo mandommi, vola con li occhi per questo giardino; ché veder lui t’acconcerà lo sguardo più al montar per lo raggio divino.» (Par. 31.94-99)

And he, the holy elder, said: “That you may consummate your journey perfectly— for this, both prayer and holy love have sent me to help you—let your sight fly round this garden; by gazing so, your vision will be made more ready to ascend through God's own ray.”

What accounts for the substitution of Beatrice by Bernard? The answer, which surely has many facets and dimensions, must include some reference to the family romance that Dante inscribes in the pages of the Commedia and thus to the roles of age and gender within that “family” of protagonists. This moment in Paradiso 31 is the second occasion in which there has been a substitution involving old/male and young/female: the first such occasion, deeply painful, occurs in Purgatorio 30, when the pilgrim is for the nonce so wounded by the loss of (old/male) Virgilio that he does not take pleasure in the arrival of (young/female) Beatrice.

This second substitution involves no pain, only mild surprise, and the direction of the substitution is reversed, as now young/female Beatrice is replaced by old/male Saint Bernard. One reason for this substitution, in effect stated by Bernard in his characterization of himself, is that the eros brought to the equation by the relationship of Dante and Beatrice would now be misplaced. Hence, for reasons that transcend personality, almost as birth order in a family is said to do, the “one” must now be replaced by “the other:” “Uno intendea, e altro mi rispuose” (Par. 31.58). In fact, a male guide and intercessor is now de rigeur, for the eros required at this junction must be directed not by Dante toward his female guide, but by a male guide toward a female intercessor.

This is precisely what occurs, as Bernard turns to the ultimate intercessor, Mary, whose devotee the saint declares himself to be:

E la regina del cielo, ond’io ardo tutto d’amor, ne farà ogne grazia, però ch’i’ sono il suo fedel Bernardo. (Par. 31.100-02)

The Queen of Heaven, for whom I am all aflame with love, will grant us every grace: I am her faithful Bernard.

Here the language of courtly love is used by Bernard for Mary, indicating that the language of courtly love used by Dante for Beatrice has been transposed: a new female intercessor has taken the place of the localized, historicized, Florentine intercessor (“di Fiorenza in popol giusto e sano”!), who has guided Dante from the time of the Vita Nuova till now.

The simile of the Croatian pilgrim who has come to Rome to view the Veronica (103-08) continues the evocation of geographical places and actual journeys and heightens the sense of a long and arduous journey that has been successfully brought to completion. Moreover, the recounting in direct discourse of the Croatian pilgrim’s thoughts as he faces the icon gives dramatic shape not only to his own mini-narrative but to the enveloping narrative of the Commedia’s pilgrim, who is nearing the point at which he too may hope to see Christ’s face.

Will there be an anthropomorphized divinity at the end of this pilgrimage? The expectation is duly raised by the simile of the Croatian pilgrim, who simply and affectingly asks himself:

Segnor mio Iesù Cristo, Dio verace, or fu sì fatta la sembianza vostra? (Par. 31.107-08)

O my Lord Jesus Christ, true God, was then Your image like the image I see now?

The family romance continues, in the idea of Christ’s face, and in that of his mother, whose face — as Saint Bernard tells Dante in the next canto — most resembles the face of Christ: “Riguarda omai ne la faccia che a Cristo / più si somiglia” (Look now upon the face that is most like the face of Christ [Par. 32.85-86]).

The new intercessor, Christ’s mother, is the queen of heaven, and Paradiso 31 ends with Dante’s attempt to lift his gaze toward the extreme radiance of her flame.

Note about the Compositional Timeline of The Undivine Comedy

Here is the historical artifact mentioned above, the old class handout from the 1980s which records my first attempt to chart the different narrative styles of the Paradiso. On the handout I still use Roman numerals for canto numbers, as I did in Dante’s Poets (published in 1984), rather than Arabic numerals as in The Undivine Comedy (published in 1992).

Return to top

Return to top