The heaven of the sun marks a new narrative beginning within the unfolding of Paradiso. It is the heaven of wisdom and the celestial home of the wise men. It is appropriate to say “wise men” because there are in fact no wise women philosophers or theologians featured in this heaven. The only female exponent of wisdom is therefore Beatrice, who claims to speak “infallibly” in Paradiso 7.19.

While the entire Commedia is a fertile site for narrative and meta-narrative analysis, these issues lend themselves to an in-depth treatment in the heaven of the sun, in part because this heaven thematizes a particular narrative genre: the saint’s life, the genre known as hagiography. Chapter 9 of The Undivine Comedy undertakes an analysis of the heaven of the sun from a narratological perspective.

The heaven of the sun is vast. It extends over almost 5 canti: Paradiso 10, 11, 12, 13, and almost two-thirds of Paradiso 14. Compare the minimal treatment of the deliberately anticlimactic heaven of Venus, which takes up only Paradiso 8 and 9.

The pilgrim is “traslato” to the heaven of Mars in Paradiso 14.83-84: “e vidimi translato / sol con mia donna in più alta salute” (I saw myself translated, alone with my lady, to higher blessedness). Outside of the shadow of the earth, the point of whose cone reaches only to the heaven of Venus (Paradiso 9.118-19), the heavens are no longer characterized negatively, via insufficiency or excess, as we have seen up to now: insufficient constancy in maintaining one’s vows in the heaven of the moon, excessive love of glory in the heaven of Mercury, excessive love of love in the heaven of Venus.

This characterization based on insufficiency or excess is reminiscent of Purgatorio 17, where we learn that all vice is love directed either toward an evil object or “with too much or too little vigor”: “o per troppo o per poco di vigore” (Purg. 17.96). And yet we are beyond all vice from the moment we enter Paradise — in fact we remember that Dante’s will is declared “free, straight, and whole” at the end of Purgatorio 27 and that he is beyond error from the moment he passes through the purging flames and enters the Earthly Paradise.

This conceptually unstable characterization, which tends to lead readers to the mistaken conclusion that there is less than perfect blessedness in the lower heavens, in the same way that readers are led by the Purgatorio’s structure to believe that the souls in Ante-Purgatory are not yet saved, is one of the classic signposts of Dante’s narrative art. He exploits narrative exigency — narrative demand for difference — to create tension in an overdetermined text, as discussed in The Undivine Comedy.

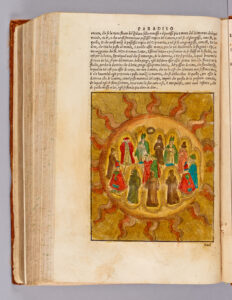

Now that we have left the shadow of the earth, the astral influences of the heavens are now expressed positively. The heaven of the sun is a celebration of wisdom. Not surprisingly, perhaps, its inhabitants — at least the ones to whom we are presented — are all male. And there are very many of them, twenty-four souls introduced by name, and we are told in Paradiso 14 of a third circle of twelve more souls whose names remain unregistered. There are many names because Dante truly celebrates wisdom in this heaven: its diversity, its many and various forms of expression.

The souls whom the pilgrim sees are arranged in circles; they are points on a circumference and, as points on a circumference, they are equidistant from the truth. The truth resides at the center of the circle, where Beatrice and Dante are positioned. The circles are concentric: the first circle of twelve souls is introduced in Paradiso 10; the second circle of twelve souls, which is introduced in Paradiso 12, forms a ring around the first circle.

The arrangement of the souls as points on a circumference that are all equidistant from the center of the circle recalls Vita Nuova 12, where Love says to Dante: “Ego tanquam centrum circuli, cui simili modo se habent circumferentie partes; tu autem non sic” (I am like the center of a circle, to which the parts of the circumference stand in equal relation; but you are not so [VN 12.4]). In the heaven of the sun Dante and Beatrice stand at the center of the circle, where Love stood in the Vita Nuova paradigm, and the blessed souls of the wise stand each equidistant from the center: each equally participatory in the truth.

This heaven is about the truth — but also, fascinatingly, about the many ways, sometimes apparently antithetical, that there are of reaching the truth. In this respect, Dante’s heaven of wisdom is a brief for intellectual tolerance.

Rhetorically, the heaven of wisdom features many examples of the rhetorical trope called chiasmus, which is ideally suited to capturing in language the idea of a “circular truth” that is composed of many balanced and integrated facets.

In rhetoric, chiasmus (from the Greek: χιάζω, chiázō, meaning “to shape like the letter c or “chi”, thus χ) is “the rhetorical trope in which one creates an imaginary cross between two sets of words, in verse or in prose, which are arranged syntactically in the scheme AB,BA” (in the Italian original: “chiasmo è la figura retorica in cui si crea un incrocio immaginario tra due coppie di parole, in versi o in prosa, con uno schema sintattico di AB,BA”).

The effort to create an χ shape with language is a move to circularize language. Two clauses or phrases are related to each other through a reversal of structures, as in AB, BA, thus displaying an inverted parallelism that provides the illusion of toward circularizing that which is inherently always linear.

As a rhetorical trope, chiasmus serves Dante as a way of balancing, equalizing, and hence “circularizing” discourse. In other words, it is a rhetorical trope that is peculiarly suited to verbalizing the theme of the heaven of the sun: through chiasmus, Dante renders the different forms of wisdom that are literally unified as the circumference of one circle.

There are many forms of chiasmi in this heaven. Not only are there many verbal chiasmi in this heaven, creating the AB, BA reversal discussed above, but most spectacularly there are the grand narrative and structural chiasmi that organize the heaven as a whole. For instance, St. Thomas, a Dominican, recounts and celebrates the life of St. Francis, and St. Bonaventure, a Franciscan, recounts and celebrates the life of St. Dominic. We will return to these structural chiasmi in the commentaries on the subsequent canti.

The Trinity is a constant presence in the heaven of wisdom, evoked in many descriptions and verbal recalls, for — embracing as it does both Three and One — it is the theological concept that best articulates this heaven’s thematic insistence on One truth composed of Many viewpoints.

A celebration of the Trinity is in fact the heaven of wisdom’s point of departure. The splendid opening of Paradiso 10 does not so much describe the Trinity as — remarkably — perform it:

Guardando nel suo Figlio con l’Amore che l’uno e l’altro etternalmente spira, lo primo e ineffabile Valore quanto per mente e per loco si gira con tant’ordine fé, ch’esser non puote sanza gustar di lui chi ciò rimira. (Par. 10.1-6)

Gazing upon His Son with that Love which One and the Other breathe eternally, the Power—first and inexpressible— made everything that wheels through mind and space so orderly that one who contemplates that harmony cannot but taste of Him.

The “living” value of the present participle with which Paradiso 10 begins — “Guardando” (Gazing) — is exemplary with respect to the performance aspect of the Trinitarian language here displayed. The first person of the Trinity (“lo primo e ineffabile Valore” the first and ineffable power) is not named until verse 3, but it is immediately present and gazing upon the second person (“suo Figlio” His Son [1]), through the agency of the third person: “l’Amore / che l’uno e l’altro etternalmente spira” (the Love which / one and the Other breathe eternally [1-2]).

The result is that the three persons of the Trinity, sequentially unfolded, are actually all contained in verse 1, held together by the magnetic force of “Guardando” (1): the gaze of the first person upon the second with the agency of the third. I write about this passage in The Undivine Comedy:

In referring to the persons of the trinity, the separateness inherent in “l’uno e l’altro” is minimized; the phrase is blanketed by its position between the participial construction of the first verse and the postponed subject of the third, the middle verse thereby serving as a pivot governing the harmonious disposition of the whole and mirroring the dialectical workings of the trinity itself. (The Undivine Comedy, pp. 200-01)

The lengthy preamble of Paradiso 10, befitting a heaven that marks a new beginning within the narrative rhythms of the Paradiso as a whole, moves to an astronomically-inflected address to the reader, as Dante directs our focus at a specific point in the cosmos. This address concludes with a key verse, in which Dante calls himself God’s “scribe”:

Or ti riman, lettor, sovra ’l tuo banco, dietro pensando a ciò che si preliba, s’esser vuoi lieto assai prima che stanco. Messo t’ho innanzi: omai per te ti ciba; ché a sé torce tutta la mia cura quella materia ond’io son fatto scriba. (Par. 10.22-27)

Now, reader, do not leave your bench, but stay to think on that of which you have foretaste; you will have much delight before you tire. I have prepared your fare; now feed yourself, because that matter of which I am made the scribe calls all my care unto itself.

This is a very important passage, which picks up from Purgatorio 24, where Dante tells us that he takes note of what Love breathes into him. From the scribe of (lyric) Love, he now effectively declares himself the scribe of the “Love that moves the sun and the other stars” — the maker of the very universe and heavens at which he now fixes his gaze.

Dante finds that he has arrived in the fourth heaven, “la quarta famiglia” (the fourth family [Par. 10.49]), in verses that offer another, more succinct, recapitulation of the Trinity:

Tal era quivi la quarta famiglia de l’alto Padre, che sempre la sazia, mostrando come spira e come figlia. (Par. 10.49-51)

Such was the sphere of His fourth family, whom the High Father always satisfies, showing how He engenders and breathes forth.

The noun “Padre” (Father) is followed by the verb “spira” (evoking the Holy Spirit) and the verb “figlia” (evoking the Son).

A circle of souls now forms a ring around the pilgrim and Beatrice. From this circle a voice emerges, beginning to speak in verse 82. This is the voice of St. Thomas. The great Dominican theologian presents the twelve souls of the first “corona” or crown (the circles of this heaven are repeatedly called “crowns” and “garlands”). These souls represent (not homogeneously, but on balance) the rationalist bent of human wisdom, whereas the second “corona” will represent (not homogeneously, but on balance) the mystical bent. See the chart below for the names of the souls in the two circles.

The first, more rationally inclined circle, has as its spokesperson Thomas, known for reconciling Aristotle with Christian theology. Next to Thomas, and the last soul he introduces, is a radical Aristotelian, Sigier of Brabant. The Averroist position of Sigier was condemned by the Bishop of Paris in his Condemnations of 1277. Sigier fled to Italy, where he died.

Dante dramatizes the multiplicity of truth in a daring way at the end of Paradiso 10, putting Sigier of Brabant within the same circle, and therefore on the same circumference, as Saint Thomas. Both are equidistant from the truth that they sought.

By saving and celebrating Sigier of Brabant, a follower of the Muslim philosopher Averroes, Dante also reminds us that he does not deem Averroes a heretic. Less than fifty years after Dante’s death, Andrea di Bonaiuto’s frescoes in the Dominican church of Santa Maria Novella in Florence will include his “Triumph of St. Thomas”, which features three heretics crouching in mortified error beneath Thomas. These three heretics are Sabellius, Arius, and Averroes. Sabellius and Arius will be mentioned as heretics in this very heaven, by St. Thomas, in Paradiso 13. Averroes, however, the central heretic in Andrea di Bonaiuto’s rendering, is in Limbo, favored as a member of Aristotle’s “filosofica famiglia” (Inf. 4.132).

And thus my title, “Multiple Truth”, echoes the so-called doctrine of the double truth: the view, attributed to Averroes and the Latin Averroists, that religion and philosophy might arrive at contradictory truths but without detriment to either. In the spirit of the heaven of the sun, this is a celebration, not of relativism, but of multiplicity — of vital difference.

Return to top

Return to top