- Dante-poet postpones his explanation of the organization of his Hell until almost one-third of the way through Inferno, waiting until Inferno 11 to explain how his Hell is structured

- Virgilio introduces the pilgrim to the “three circles” that lie below: the circle of violence, the circle of fraud practiced on those who do not have reason to trust you, and the circle of fraud practiced on those who do have reason to trust you, i.e. betrayal

- Introducing the structure of his Hell, Dante affirms the principle of difference that will be so important in Paradiso

- The treatment of violence offers an implied positive evaluation of material goods, which we should factor into our evaluation of Dante’s thinking about wealth

- Dante-pilgrim asks Virgilio about the previous circles of Hell, those outside the city of Dis

- Each sin of upper Hell, with the exception of Limbo, is evoked in a tagline that distills its Dantean contrapasso

- These intratextual citations — the Inferno is citing the Inferno — enhance the text’s truth claims and the perceived “reality” of Dante’s Hell

- Dante’s strong personal connection to Aristotle’s works, which are carefully named: “la tua Etica” (your Ethics [Inf. 11 80]) and “la tua Fisica” (your Physics [Inf. 11.101])

- The word “incontinenza” — lack of misura, moderation, or self-restraint — is used only in this canto: it is the technical Aristotelian term, the Italian translation of the Latin “incontinentia”, and the analogue to the vernacular term “dismisura”

- An exposition of the principle of mimesis, here Christianized

[1] Inferno 11 is not a dramatic canto. It can seem rather dry, since it is devoted to outlining the structure of Dante’s Hell. But Dante’s apparently dry content has very juicy implications — in both the narrative/diegetic and the ideological/ cultural domains.

[2] Inferno 11 begins by announcing that the travelers have reached the outer perimeter of the sixth circle. They have come to the edge of a steep cliff and, while acclimating their olfactory senses to the formidable stench that comes from the abyss below, Virgilio describes the structure of Hell.

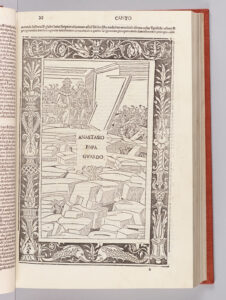

[3] They draw back from the edge, and from the emanating stench, until they are by the lid of a great tomb, on which is inscribed “Anastasio papa guardo, / lo qual trasse Fotin de la via dritta” (I hold Pope Anastasius, / enticed to leave the true path by Photinus [Inf. 11.8-9]). In this tomb is Pope Anastasius II, who died in Rome in 498 CE. In Dante’s time it was believed, following the Liber pontificalis and Gratian’s Decretum, that Pope Anastasius had succumbed to the monophysite heresy of patriarch Acacius of Constantinople, holding that Christ had only a human nature and not a divine one, and that he had been led to that heresy by the deacon Photinus. This sighting of the tomb of Anastasius II is the final installment of the sixth circle, focused on heresy.

[4] The travelers decide to delay their descent to the lower regions of Hell until they become accustomed to the foul smell emanating from the pits below them. In order to put this pause in their journey to good pedagogical ends, Virgilio decides to take this opportunity to discourse on the structure of the infernal underworld through which they are journeying. This pause with its significant discursive content extends from verse 16 of Inferno 11 to the canto’s end.

[5] Narratologically, Inferno 11 reveals a canny and interesting choice on Dante-poet’s part: he has delayed the exposition of the structure of his Hell. Not until we are one-third of the way through Inferno does Dante offer his readers the guidance provided by an organizational template of Hell. What are Dante’s reasons for postponing an explanation of the ideological basis of his Hell?

[6] I suggest that Dante-poet first entices his readers to believe that he is following a standard Christian template for organizing his Hell, and now surprises his readers with information that gives unusual, indeed anomalous, dignity to the pagan authority from whom he borrows the ethical categories for structuring his Hell. Thus, Dante-poet first delays his exposition, offering no guidance to his readers, and then offers as guidance what his readers could never have expected: the categories and ideas of Aristotle, In this way, Dante-poet uses his narrative choices to underline his anomalous ideological choices.

[7] A Christian template that the readers might expect would be one based on the seven deadly sins (more accurately known as the seven deadly vices). The reader of Inferno might well have thought that Dante was using the seven vices as his template; for, as we pass through the early circles of his Hell, we pass through lust, gluttony, avarice, sloth, and anger, in precisely the order that conforms to the hierarchy of deadly vices.

[8] However, as I discuss in the Commento on Inferno 7, an attentive reader could infer that Dante has deviated from the template of the seven vices by the time we reach the fourth circle, where instead of finding only avarice, as per the seven vices, we find avarice paired with prodigality. The implications of including prodigality along with avarice in the fourth circle are already suggested in Inferno 7, and are subsequently fully unveiled in Inferno 11: the source that Dante-poet uses to construct his Hell is Aristotle. This is hugely significant information. No previous (or subsequent) Christian afterlife vision invokes a classical philosopher as its authority on ethics, and hence as its authority for the organization of Hell.

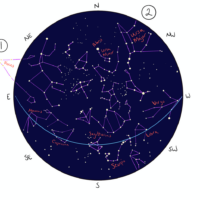

[9] In verse 16 Virgilio begins his explanation of what the pilgrim will find as they proceed downwards, offering first the information that there are three more circles in Hell, like the ones they have left behind. These circles become progressively smaller as they get lower: “son tre cerchietti / di grado in grado, come que’ che lassi” (there are three smaller circles; / like those that you are leaving, they range down [Inf. 11.17-18]). This is incongruous information: we are not yet half-way through Inferno, and yet we have passed through six circles and only three remain? And the circles that remain are “cerchietti” (little circles)?

[10] Like the circles that we have passed through, the three circles that remain continue to diminish in circumference, because Hell is shaped like a funnel that gets narrower until finally it reaches a point at the center of the earth, a point that is first referenced in this very canto in verses 64-65. But the three circles that remain do not get smaller in terms of storage capacity and overall size, for they are complex and subdivided in ways that we have not seen heretofore. As a result of their structural complexity, the lower circles are very capacious in terms of the number of souls they can house.

[11] Virgilio lays out the ethical distinctions that provide, first, the intellectual basis for the last three circles of Hell, and subsequently, over the course of Inferno 11, provide the intellectual basis for all of Hell. Beginning in verses 22-24, he explains that all sins of malice seek injustice, but can do so in two ways, either through the deployment of force or through the deployment of fraud: “ed ogne fin cotale / o con forza o con frode altrui contrista” (and each such end / by force or fraud brings harm to other men [Inf. 11.23-4]). Because fraud is mankind’s peculiar vice, depending as it does on reason, it displeases God more than force, and thus the circle of fraud is lower than the circle of violence: “più spiace a Dio; e però stan di sotto / li frodolenti, e più dolor li assale” (God finds it more displeasing — / and therefore, the fraudulent are lower, suffering more [Inf. 11.26-7]).

[12] Having established that fraud is further down in Hell than violence, Virgilio immediately derives the implications of this fact, which he does by referring to and then describing a place that he calls the “first circle” in verse 28. With the label “pimo cerchio” Virgilio here refers not to the first circle of Hell (which we know is Limbo), but to the first circle that the travelers will find below them, thus the seventh circle of Hell, which he tells us is all devoted to the violent: “Di vïolenti il primo cerchio è tutto” (The violent take all of the first circle [Inf. 11.28]).

[13] Virgilio proceeds to divide the circle of violence into three sections, depending on whether the violence done is to one’s neighbor, to one’s self, or to God (Inf. 11.31). He then further subdivides these three sections by adding another distinction: one can do violence in each of the three categories of neighbor, self, and God in two distinct ways, either to the person of neighbor, self, or God, or to the person’s possessions (Inf. 11.32). The result is that the seventh circle is divided into three rings, and that each ring houses two modalities of the same kind of violence.

[14] The first ring, which the pilgrim enters in Inferno 12, houses violence against one’s neighbors. When applied to the persons of others, such violence results in “Morte per forza e ferute dogliose” (Violent death and painful wounds [Inf. 11.34]); those who commit such violence are “omicide e ciascun che mal fiere” (murderers and those who strike in malice [Inf. 11.37]). Violence against one’s neighbors in their possessions results in “ruine, incendi e tollette dannose” (ruin, fire, and extortion” [Inf. 11.36]), and is committed by “guastatori e predon” (plunderers and robbers [Inf. 11.38]).

[15] The second ring, which the pilgrim enters in Inferno 13, punishes violence against one’s self. Practiced against one’s person, this form of violence involves “setting violent hands upon oneself” — “avere in sé man vïolenta” (Inf. 11.40) — and results in suicide, given that the sinner “priva sé del vostro mondo” (deprives himself of your world [Inf. 11.43]). Practiced against one’s possessions, the setting of violent hands upon one’s goods results in dissipation: “biscazza e fonde la sua facultade” (he gambles away and wastes his patrimony [Inf. 11.44]).

[16] The third ring houses the violent against God and is spatially the most extensive, comprising Inferno 14-17. The textual space devoted to the third ring of violence reflects the conceptual complexity of this section, rendered complex by Dante’s handling of the issue of God’s possessions. To be violent toward God’s possessions involves being violent toward nature (resulting in the sin of sodomy) and toward nature’s offspring, human art or techne (resulting in the sin of usury). The explanation given is opaque and therefore results in a further question about the sin of usury posed by the pilgrim toward the end of Inferno 11, in verses 95-96. Virgilio’s reply, in which he explains God’s two possessions, is also complex and extends from verse 97 to verse 111.

[17] The violent against God in His person are the blasphemers, who “deny the deity in their hearts and blaspheme it”: “col cor negando e bestemmiando quella” (Inf. 11.47). The pilgrim encounters the blasphemers in Inferno 14. The violent against God in his possessions “scorn nature and her goodness”: “spregiando natura e sua bontade” (Inf. 11.48). The sins of scorning nature and her goodness are sodomy and usury, referenced by Virgilio very succinctly through the names of two cities that are symbols of the sins practiced by their inhabitants: “e Soddoma e Caorsa” (both Sodom and Cahors [Inf. 11.50]). The sin of sodomy was practiced in the biblical city of Sodom (from which the word “sodomy” is derived), the evil city destroyed by God in Genesis, whereas the contemporary French city of Cahors was notorious for its usurers, called indeed “caorsini”.

[18] It is interesting that both violence against others and violence against the self feature the abuse of material goods. Dante’s language in this passage stresses the possessions and material goods that are subjected to violent treatment: “in lor cose” (in their things [Inf. 11.32]), “nel suo avere” (in his possessions [35]), and “ne’ suoi beni” (in his goods [41]). It is important to note that material goods are here viewed not as objects of disdain and reprehension, as we might associate with some strains of Christian belief, for instance among the Franciscans, but rather as objects of value that must be protected from human violence. Dante’s taxonomy of violence thus harbors a positive evaluation of material goods, implicit in the idea that material goods should be protected from violent depredation.

[19] Dante’s treatment of violence is another indication of the Aristotelian mode of Inferno 11, a mode that distances Dante’s thought in this canto from other approaches toward material goods, also represented in the Commedia, such as the ferocious position that Dante takes against papal wealth. As I discuss in the essay “Dante and Wealth, Between Aristotle and Cortesia” (cited in Coordinated Reading), there are extremely divergent perspectives on wealth and material possessions that coexist in the Commedia. We must be careful to separate the different threads of the poet’s thought and not conflate them.

[20] Having made an oral outline of the sins of violence for the pilgrim, one that extends from verse 28 to verse 51, Virgiio turns in verse 52 to the sins of fraud. His first move is to divide fraud into two large categories: there is fraud practiced against those who trust us, and fraud practiced against those who do not trust us (Inf. 11.52-54). The forms of fraud practiced on someone with whom one does not have a special bond of trust are to be found in circle 8, while fraud practiced against those with whom one does have a special bond of trust is betrayal, located in circle 9, the lowest circle in Dante’s Hell.

[21] Virgilio then indicates the kinds of fraud that will be found in lower Hell’s “second circle” (“cerchio secondo” in verse 57 links back to “primo cerchio” used for the circle of violence in verse 28). Without proceeding in order through the ten bolge or sacks of the eighth circle, and without listing all ten of the bolge, Virgilio tells the pilgrim that the circle of fraud contains: “ipocresia, lusinghe e chi affattura, / falsità, ladroneccio e simonia, / ruffian, baratti e simile lordura” (hypocrisy and flattery, sorcerers, / and falsifiers, simony, and theft, / and barrators and panders and like trash [Inf. 11.58-60]).

[22] Virgilio concludes by telling Dante that the traitors of circle 9 are located in the “cerchio minore” (Inf. 11.64), the third and smallest of the “tre cerchietti” (three little circles) of lower Hell with which Virgilio’s exposition begins (verse 17). The traitors are housed with Lucifer (also known as Dis, cf. “Dite” in Inf. 11.65), whose seat is at the center of the universe, in the very bottom-most pit of Hell.

[23] Virgilio had mentioned going to the very bottom of Hell in Inferno 9. At that time he explained to Dante that he was conjured by the sorceress Erichtho, who constrained him to go to the “cerchio di Giuda” (Judas’ circle [Inf. 9.27]), described as “’l più basso loco e ’l più oscuro, / e ’l più lontan dal ciel che tutto gira” (the deepest and the darkest place, / the farthest from the heaven that girds all [Inf. 9.28-29]).

[24] Armed with new information, we now know that, in going to the deepest circle, farthest from heaven, Virgilio was going to the “smallest circle”, the circle that houses traitors. It is the place that holds the soul of Judas (the “Giuda” of “cerchio di Giuda” in Inf. 9.27), who betrayed Jesus for thirty pieces of silver. It is the place where Lucifer, aka Dis, resides, sitting on this very point, at the center of the universe: “onde nel cerchio minore, ov’ è ’l punto / de l’universo in su che Dite siede” (thus, in the tightest circle, where there is / the universe’s center, seat of Dis [Inf. 11.64-65]).

[25] The taxonomic structure of the circle of fraud is far less complex than that of violence, since it does not boast the division and subdivision that we find in the circle of violence. Rather than taxonomically complex, fraud is massive. Fraud occupies almost one-half the real estate of Hell: the pilgrim enters the eighth circle in Inferno 18 and leaves the ninth circle when he leaves hell in Inferno 34.

[26] At this point, there is an interruption in the linear progression of Virgilio’s masterful lesson. Now the student interjects a question. He wants to know why the sinners whom they have seen on their journey thus far are not within the “red city”, the city of Dis: “perché non dentro da la città roggia / sono ei puniti, se Dio li ha in ira?” (why are they not all punished in the city / of flaming red if God is angry with them? [Inf. 11.73-74]).

[27] Reasoning on the premise that, if God holds a soul in anger, that person will be “within” the city of Dis, in other words, within lower Hell, the pilgrim is puzzled as to why the many damned souls whom he saw prior to arriving at the enflamed towers of Dis are not imprisoned within its walls. In her commentary, Chiavacci Leonardi argues that the pilgrim’s comment makes sense if one believes that all sins are of equal gravity: “L’obiezione ha senso se parte dal presupposto che tutti i peccati siano di eguale gravità di fronte a Dio, opinione che era stata propria degli stoici e di alcuni eretici” (The objection has sense if it starts from the presupposition that all sins are of equal gravity in front of God, the opinion of the Stoics and of some heretics [Chiavacci Leonardi, Inferno, ad loc]).

[28] Chiavacci Leonardi’s suggestion that the pilgrim here questions the very existence of a hierarchical distinction between sins is not convincing, given that in the upper circles as well the poet has clearly signalled the increase of gravity that occurs with each descent:

Così discesi del cerchio primaio giù nel secondo, che men loco cinghia e tanto più dolor, che punge a guaio. (Inf. 5.1-3)

So I descended from the first enclosure down to the second, that which girdles less space but grief more great, that goads to weeping.

[29] However, I fully endorse the spirit of Chiavacci Leonardi’s observation, since it highlights the importance of difference and gradation in Dante’s Hell. Dante-pilgrim asks a somewhat awkward and naïve question in order to justify the poet in his clarion call to difference and distinction, which rings out through Inferno 11, a canto in which the poet offers a concentrated introduction to the language of difference, the very language of più e meno that will dominate much of Paradiso:

Inferno 11 [is] the canto that expounds difference, clustering quantifiers in an effort to give verbal shape to the hierarchy of Hell: “tre cerchietti” (three little circles [17]), “primo cerchio” (first circle [28]), “tre gironi” (three rings [30]), “lo giron primo” (the first ring [39]), “secondo /giron” (second ring [41-42]), “cerchio secondo” (second circle [57]). We find as well an impressive spate of the adverbs first used in canto 5 to render difference, più and meno: since fraud “più spiace a Dio” (displeases God more [26]), the fraudulent are assailed by “più dolor” (more suffering [27]); since incontinence, on the other hand, “men Dio offende e men biasimo accatta” (offends God less and incurs less blame [84]), God’s vengeance is “men crucciata” (less wrathful [89]) in smiting such sinners. We find expressions that convey difference geographically, dividing those who are below and within from those who are above and without: while the fraudulent “stan di sotto” (are below [26]), the incontinent are not within the city of Dis, “dentro da la città roggia” (inside the flaming city [73]) but “sù di fuor” (up outside [87]). We find phrases like “di grado in grado” (from grade to grade [18]) and “per diverse schiere” (in different groups [39]), and verbs that denote differentiation, such as distinguere and dipartire: the circle of violence “in tre gironi è distinto” (is divided into three rings [30]), and the incontinent are “dipartiti” (divided [89]) from the souls of lower Hell. (The Undivine Comedy, p. 45)

[30] Virgilio’s discourse on the structure of Hell in Inferno 11 is the Commedia‘s first concentrated discursive act of differentiation, linguistically prefiguring the great creation discourses of Paradiso. When Virgilio explodes in annoyance at the pilgrim’s silly question in verses 76-77, he essentially asks how Dante can have failed to grasp the principle that underlies all created existence: the principle of difference. The lexicon of differentiation that saturates Inferno 11 will be reprised, strangely but coherently, in Paradiso, the canticle that focuses on creation and created existence.

[31] Let us backtrack to look more closely at the pilgrim’s query and Virgilio’s response. The pilgrim’s query is noteworthy as a moment of remarkable intratextual density, for, in order to express his puzzlement about the souls he witnessed prior to arriving at the city of Dis, Dante-pilgrim uses a shorthand fashioned from the fiction written by Dante-poet. Going back mentally over the landscape of Hell that he and Virgilio have already traversed, the pilgrim designates the souls of circles 2-5 using a shorthand based on the contrapasso of each circle:

Ma dimmi: quei de la palude pingue, che mena il vento, e che batte la pioggia, che s’incontran con sì aspre lingue, perché non dentro da la città roggia sono ei puniti? (Inf. 11.70-74)

But tell me: those the dense marsh holds, or those driven before the wind, or those on whom rain falls, or those who clash with such harsh tongues, why are they not all punished in the city of flaming red if God is angry with them?

[32] In the above verses Dante accounts for all the circles of upper Hell with the exception of the first, Limbo. Like the sixth circle, heresy, Limbo is omitted from Virgilio’s account of hell in Inferno 11, presumably because neither are ethical sins in the sense intended by Aristotle’s Ethics. The two circles not included focus instead on Christianity, and involve either failures toward Christianity (Limbo) or violations of its tenets (heresy), and they are therefore omitted from the Aristotelian accounting of Inferno 11.

[33] Verses 70-72 designate each circle of upper Hell (excepting the first) through periphrases that are distilled from infernal torments, here condensed into pithy individual taglines. In this way these verses find a way to include circles 2-5 in the canto that is devoted to explaining the structure of Hell as a whole. They do this by vividly recapitulating the sins of the circles not discussed in Inferno 11, for the catchphrases bring to mind each sin of upper Hell. Here are Dante’s evocations of the sins of circles 2-5, in the order in which the author presents them in Inferno 11.70-72:

- Verse 70: “quei de la palude pingue” (those of the muddy marsh): a reference to Styx, the swamp that holds the accidiosi and the wrathful => circle 5

- Verse 71: “che mena il vento” (those whom the wind drives): a reference to the contrapasso of the circle of lust => circle 2

- Verse 71: “e che batte la pioggia” (those whom the rain beats): a reference to the contrapasso of the circle of gluttony => circle 3

- Verse 72: “e che s’incontran con sì aspre lingue” (those who clash with such harsh tongues): a reference to the contrapasso of the misers and the prodigals => circle 4

[34] These intratextual citations — the Inferno is citing the Inferno — are, moreover, a technique of verisimilitude. These citations treat the textual account as “real” and thereby enhance the text’s truth claims and the “reality” of Dante’s Hell.

[35] How does Virgilio answer the pilgrim’s question as to why the sins listed above are not included within the city of Dis? Virgilio asks Dante, with some asperity, why his reason has wandered so far from its accustomed course. He then wonders whether Dante has forgotten those words in the Ethics in which the philosopher treats the three dispositions that heaven condemns. These three dispositions are, in Latin, “malitia, incontinentia, et bestialitas” (Ethics 7.1.1045a), and are rendered by Dante in Italian thus:

incontenenza, malizia e la matta bestialitade? e come incontenenza men Dio offende e men biasimo accatta? (Inf. 11.82-84)

incontinence and malice and mad bestiality? And how incontinence offends God less and acquires least rebuke?

[36] With the phrase “Non ti rimembra di quelle parole / con le quali la tua Etica pertratta / le tre disposizion” (Inf. 11.79-80), Virgilio is instructing Dante to recall the beginning of Book 7 of Nicomachean Ethics, where Aristotle affirms that “of moral states to be avoided there are three kinds — vice, incontinence, brutishness”.

[37] Presuming that these three Aristotelian categories have been adapted by Dante to his Hell, and that with the term “malizia” he intends to refer to the sins of fraud, whereas with “bestialitade” he intends to embrace the sins of violence,[1] we turn now to the concept of incontinence. Dante here uses the technical label “incontinentia” (the Latin translation of the Aristotle’s Greek akrasia); he uses the term twice in Inferno 11, in verses 82 and 83, and nowhere else. The sins of incontinence, Virgilio states, are those that offend God less; for that reason, the incontinent are punished in upper Hell, outside of the city of Dis.

[38] By “incontinence”, Dante, like Aristotle, refers to lack of moderation and self-restraint. The sins of incontinence are sins of excessive and immoderate desire, of desire that is not moderated by virtue. In Inferno 7, where Dante uses an Aristotelian template for a thinking about the human relationship to material goods and wealth, he describes the misers and the prodigals as those who have no “misura” in their spending. In my Commento on Inferno 7 I propose that the vernacular terms misura and dismisura are analogues of the Aristotelian continenza and incontinenza.

[39] As noted above, the pilgrim asks for an explanation of usury in verses 94-96, asking Virgilio to go back in his mind to where he had said that usury offends divine goodness and to resolve the knot:

“Ancora in dietro un poco ti rivolvi”, diss’io, “là dove di’ che usura offende la divina bontade, e ’l groppo solvi”. (Inf. 11.94-96)

“Go back a little to that point”, I said, “where you told me that usury offends divine goodness; unravel now that knot”.

[40] Here the pilgrim speaks not elliptically of the city of Cahors, as Virgilio had, but openly about “usura”: “là dove di’ ch’usura offende” (Inf. 11.95). In this way Dante introduces one of the Commedia’s two uses of usura (see Par. 22.79 for the other occasion), which will be shortly followed by the poem’s only use of “usuriere” (usurer) in Inferno 11.109.

[41] To resolve the knot of God’s two possessions, nature and art, Dante offers a genealogy of sorts, one that involves God’s “daughter” (nature) and “grandchild” (human art, skill, techne). This genealogy is based on the principle of mimesis (Greek) or imitatio (Latin). The first tenet is that nature “takes its course” from God. In other words, nature follows God: “natura lo suo corso prende / dal divino ’ntelletto e da sua arte” (nature takes her course from / the Divine Intellect and Divine Art [Inf. 11.99-100]).

[42] The second tenet is that, similarly, human art follows nature:

l’arte vostra quella, quanto pote, segue, come ’l maestro fa ’l discente; ì che vostr’arte a Dio quasi è nepote. (Inf. 11.103-5)

Your art follows nature, when it can just as a pupil imitates his master; so that your art is almost God’s grandchild.

[43] Dante expresses the principle of imitation most clearly in the simile of verse 104, where he claims that our art follows nature in the way that a pupil follows a teacher.

[44] Dante here constructs a genealogy — nature is God’s child and human art is God’s grandchild — that is also a theory of art: we note the transition from the Divine Art in verse 100 to “your art” in verse 103. As such, it is a theory of realism that is essential for understanding Dante’s view of his own art. He is a poet who heroically strives to imitate nature/reality to the best of his ability, “sì che dal fatto il dir non sia diverso” (so that my word not differ from the fact [Inf. 32.12]). We see here a Christianizing of the Aristotelian concept of mimesis, whereby art imitates nature.

[45] Dante had already alluded to this doctrine in a Christian context in his linguistic treatise De vulgari eloquentia, where he presents the building of the Tower of Babel by the biblical king Nembrot as an act of hubris. Nembrot’s arrogance involved trying “to surpass with his art not only nature, but also nature’s maker, who is God”:

Presumpsit ergo in corde suo incurabilis homo, sub persuasione gigantis Nembroth, arte sua non solum superare naturam, sed etiam ipsum naturantem, qui Deus est. (De vulgari eloquentia 1.7.4)

So uncurable man, persuaded by the giant Nembrot, presumed in his heart to surpass with his art not only nature, but also nature’s maker, who is God.

[46] In linking “art”, “nature”, and “nature’s maker, who is God” in the De vulgari eloquentia’s account of the Tower of Babel, Dante effectively expounds the same mimetic hierarchy that is later presented in Inferno 11: at the top of the hierarchy is God, who is nature’s maker, followed by nature, which follows God, followed by human art, which follows nature.

[47] Dante’s grasp of the concept of mimesis does not come directly from Aristotle’s Poetics, a work not yet available in the West, but is a distillation of Aristotelian doctrine. Virgilio beings his answer in verse 97 with the word “Filosofia”: philosophy, he says, notes how nature follows the divine intellect and its workings, “come natura lo suo corso prende / dal divino ’ntelletto e da sua arte” (how nature follows, as she takes her course / the Divine Intellect and Divine Art [Inf. 11.99-100]). For the principle that human art follows nature, Virgilio sends Dante specifically to Aristotle’s Physics:

e se tu ben la tua Fisica note, tu troverai, non dopo molte carte, che l’arte vostra quella, quanto pote, segue (Inf. 11.101-4)

and if you read your Physics carefully, not many pages from the start, you’ll see that when it can, your art would follow nature

[48] From Physics 2.2.194a, the scholastics extracted the idea that was distilled in medieval anthologies as follows: “ars imitatur naturam in quantum potest” — literally, art imitates nature as much as it can. Virgilio’s instructions are precise, indicating that the desired passage will be found “non dopo molte carte” (not many pages from the start [Inf. 11.103]), and indeed the passage in question is in Physics Book 2. Moreover, as with “la tua Etica” in verse 80, Virgilio again prefaces Aristotle’s work with the pronoun “tua”: “la tua Fisica” (101).

[49] Thus, Inferno 11 offers two texts of Aristotle’s by name, as “your Ethics” and “your Physics”. By attaching the pronoun “tua” first to Aristotle’s Ethics and then to his Physics, Dante indicates the profound personal connection — affective and intellective — that binds him to the great philosopher’s thought.

[50] As in Inferno 4, the canto that treats Limbo and its virtuous pagans, a group never before connected to Limbo in Christian theology, so in Inferno 11: both canti are apparently dry but pulse with emotion, in this case concentrated in the pronoun “tua” in “la tua Etica” and “la tua Fisica”. The taxonomy of Hell offered in Inferno 11 becomes the poet’s opportunity to put himself in an ethical and philosophical genealogy headed by Aristotle, as in Inferno 4 he puts himself in the poetic genealogy of the bella scola headed by Homer.

[51] But the Physics is not the last text cited in Inferno 11. Virgilio glosses the concept of usury further by invoking Genesis:

Da queste due, se tu ti rechi a mente lo Genesì dal principio, convene prender sua vita e avanzar la gente; e perché l’usuriere altra via tene, per sé natura e per la sua seguace dispregia, poi ch’in altro pon la spene. (Inf. 11.106-11)

From these two, art and nature, it is fitting, if you recall how Genesis begins, for men to make their way, to gain their living; and since the usurer prefers another pathway, he scorns both nature in herself and art, her follower; his hope is elsewhere.

[52] We see that Dante explicitly evokes “the beginning of Genesis” — “lo Genesì dal principio” — referring to Genesis 3:17-19 where God condemns man to toil and to eat by the sweat of his brow. The usurer, in attempting to live without toil, “scorns both nature in herself and art, her follower” (Inf. 11.111).

[53] The final section of Inferno 11 thus effectively brings together Aristotle and the Bible: in verse 101 we find a reference to the Physics and in verse 107 a reference to Genesis. The convergence of Aristotle with Genesis at the end of Inferno 11 is an extraordinary testament to the Commedia’s richly multicultural program. Both classical and biblical are evidenced in Inferno 11’s unique treatment of the organizational structure of Hell. But the authority whom Dante stipulates as his source for hell is unequivocally classical: “ ’l maestro di color che sanno” (Inf. 4.131).

[1] Although there have been many arguments put forth, this is the concensus position, and one that goes back to antiquity. See the excellent note in Chiavacci Leonardi.

Appendix

Outline of the Structure of Hell, as Presented in Inferno 11

[Circle 1: Limbo (Inferno 4): omitted from Inferno 11]

Circles 2-5: Sins of Incontinence

- circle 2) lust (Inferno 5)

- circle 3) gluttony (Inferno 6)

- circle 4) avarice and prodigality (Inferno 7)

- circle 5) tristitia and anger (end of Inferno 7, Inferno 8)

[Circle 6: Heresy (Inferno 10): like Limbo, omitted from Inferno 11]

Circle 7: Sins of Violence, 3 types of violence, each further inflected in 2 ways, as violence against a person and violence against a person’s possessions

- Type 1: Violence against one’s neighbor (Inferno 12): modality 1) against the neighbor’s person, e.g. murder; modality 2) against the neighbor’s possessions, e.g. robbery

- Type 2: Violence against oneself (Inferno 13): modality 1) against one’s person, e.g. suicide; modality 2) against one’s possessions, e.g. squandering

- Type 3: Violence against God (Inferno 14-17): modality 1) against God’s person, e.g. blasphemy (Inferno 14); modality 2a) against God’s first possession, His “daughter” nature, e.g. sodomy (Inferno 15-16); modality 2b) Violence against God’s second possession, His “grandchild” human art (skill, endeavor), e.g. usury (Inferno 17)

Circles 8 and 9: Fraud, practiced on those who have no reason to trust you (circle 8), and practiced on those who do have reason to trust you (circle 9)

Circle 8 is subdivided into 10 categories:

- pimping and seduction (Inferno 18)

- flattery (Inferno 18)

- simony, corruption of the Church (Inferno 19)

- false prophesy (Inferno 20)

- graft/corruption of the state (Inferno 21-22)

- hypocrisy (Inferno 23)

- fraudulent thievery (Inferno 24-25)

- false counsel (Inferno 26-27)

- sowing of discord (Inferno 28)

- falsifiers of metals, persons, coins, and words (Inferno 29-30)

Circle 9: Fraud, practiced against those who have reason to trust you, i.e. Betrayal, divided into 4 categories

- Betrayal of family (Inferno 32)

- Betrayal of political party (Inferno 32-33)

- Betrayal of guests (Inferno 33)

- Betrayal of benefactors (Inferno 34)

Return to top

Return to top