Of the two canti devoted to the encounter with Stazio, Purgatorio 21 is perhaps the more emotional and personal, ending with the poignant revelation of Virgilio to Stazio. Purgatorio 22 on the other hand builds on Purgatorio 21 to create the iron-clad vise of a painful paradox: we witness a superior human being who is not saved, and who guides others (less superior on the human scale of values) to salvation.

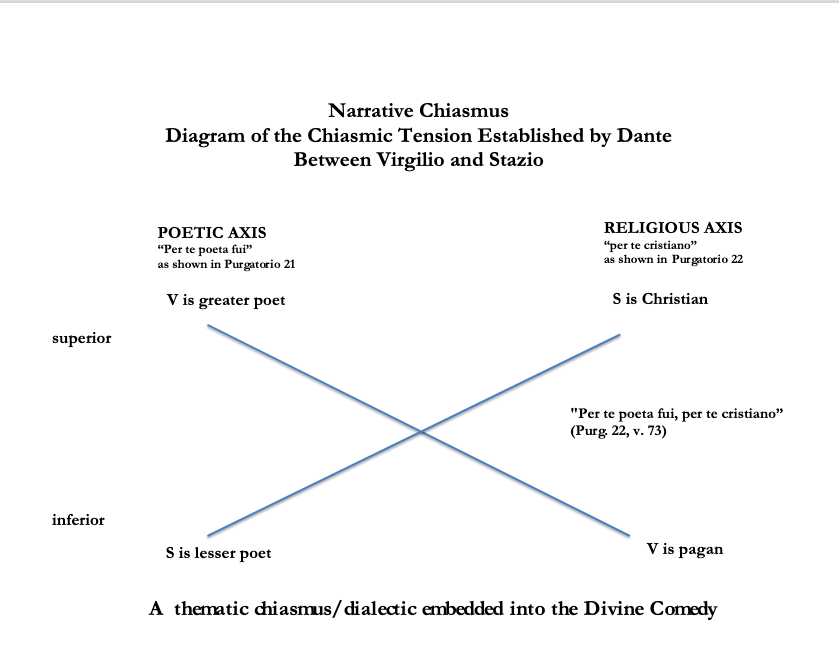

There are two documents included here. One is the diagram “Narrative Chiasmus”, in which I try to visualize how Dante locks us into his paradox around the two axes that are articulated in Stazio’s great tribute: “Per te poeta fui, per te cristiano” (Through you I was a poet and, through you, a Christian [Purg. 22.73]).

The structural chiasmus around which Dante-poet models the Virgilio-Stazio interaction is reminiscent of the narrative chiasmus that unfolds in the depiction of the character Virgilio, who is the more loved by the pilgrim as his pedagogical limitations are revealed by the poet.

The thematic and structural chiasmus that undergirds the Virgilio-Stazio interaction is composed of two axes: one axis is that of poetry and human greatness (“per te poeta fui”), and the other axis is that of belief and religious conviction (“per te cristiano”). In his commentary to the Commedia the great fourteenth-century literary scholar-critic Benvenuto da Imola writes: “but whether he [Statius] was a Christian, or whether he was not, I care little, since subtly and by necessity the poet feigns this because of the many issues he could not treat without a Christian poet, as will appear in canto XXV and elsewhere.”

I cite Benvenuto in Dante’s Poets, and then add my complete endorsement of his view: “In this remarkable passage Benvenuto goes, as he so often does, to what I believe is the heart of the matter, which is that Dante’s fiction at this point requires a figure just like Statius. In fact, Dante needs a foil to Vergil, a role for which the Christianized Statius is carefully tailored, as the character who can best bring out the ambivalence of Vergil’s situation: whereas Statius the epic poet is Vergil’s inferior, his disciple, the Statius who became Christian is Vergil’s superior, his teacher” (Dante’s Poets, p. 258). What is remarkable is Benvenuto’s critical sophistication, his recognition that a poet of Dante’s genius and originality will not demur at creating what he needs to make his narrative point — and that what he needs now is a Latin poet who happens to be Christian and who profoundly reveres the poet who wrote the Aeneid.

With that formula Dante is able to raise the narrative tension that has been ever present in the figure of the guide who is both beloved and damned, and to capture that tension in the verse “Per te poeta fui, per te cristiano” (Purg. 22.72). The verse delineates a chiasmic tension that is embodied in the two figures, Stazio and Virgilio, which I endeavor to visualize below.

The second document that I attach, and that you will find below, is “Dante’s Vergil”. This is a catalogue of the various ways in which Vergilian texts are used as intertexts in the drama of Purgatorio 22 and throughout the Commedia. As you can see, the modalities that Dante devises for the use of Vergilian texts are complex, and the catalogue ranges from allusion to translation to verbatim citation.

The second document that I attach, and that you will find below, is “Dante’s Vergil”. This is a catalogue of the various ways in which Vergilian texts are used as intertexts in the drama of Purgatorio 22 and throughout the Commedia. As you can see, the modalities that Dante devises for the use of Vergilian texts are complex, and the catalogue ranges from allusion to translation to verbatim citation.

(Please refer to this document for the details of the textual issues that I will outline broadly in this commentary.)

Purgatorio 22 is deeply invested in classical culture, indeed in the salvific effects of classical culture. Before we get to the details of the Stazio problematic, let us note that classical culture — Aristotle in fact — is present from the outset of the canto. Aristotle provides our cultural frame of reference from the moment we learn that this is not the terrace of simply avarice, as per the Christian scheme of the seven capital vices, but that it is the terrace of avarice and prodigality.

In the Christian scheme of the seven deadly vices, the scheme that provides the template for the seven terraces of Purgatory, there is no composite vice of avarice and prodigality. There is only the vice of avarice. The decision to make the fifth terrace the terrace of avarice and prodigality, following the model of the circle of avarice and prodigality in Hell (see Inferno 7), is stunning. It shows that Dante’s commitment to Aristotelian ethics is indeed profound. It is already remarkable that in Inferno 11 Dante tells us that his Christian Hell is organized according to the template provided by Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. Now in Purgatory he continues to show his fascination with the Aristotelian idea of virtue as not an extreme but a mean.

We can see Dante playing with two ethical systems — the Aristotelian ternary system and the Christian binary system — and think of this as a profound instance of his cultural hybridity. The Christian system of the seven capital vices is now contaminated by another system, whereby virtue is the golden mean between the two sinful extremes of avarice and prodigality.

In Hell, Dante classifies the sins of excess desire with the Aristotelian rubric “incontinence”. The term “incontenenza” appears exclusively in Inferno 11, the canto that reveals Dante’s appropriation of Aristotle’s Ethics in devising the moral structure of Hell. In Purgatorio 22, there is no overt claim of dependence on Aristotle, and Dante employs the vernacular equivalent of the term “incontenenza”, which is “dismisura” (35).

However, while the Aristotelian term “incontenenza” is used only in Inferno 11, never in Purgatorio, there is an allusion to incontinence in the taxonomy of vice in Purgatorio 17. Here we find the category of love pursued with too much vigor (“con troppo di vigore”), and in this category are the very sins of incontinence that we saw in Hell:

lust = circle 2 of Hell (Inferno 5)

gluttony = circle 3 of Hell (Inferno 6)

avarice/prodigality = circle 4 of Hell (Inferno 7)

In Purgatorio we find the same categories, but in inverted order. Instead of descending with the gravitational pull of sin from less bad to more bad, we are ascending away from the weight of sin toward lightness and freedom from vice:

avarice/prodigality = terrace 5 of Purgatory

gluttony = terrace 6 of Purgatory

lust = terrace 7 of Purgatory

In essence, Purgatorio 22 pivots around two questions posed by Virgilio to Stazio, both of which elicit a pagan text as a reply. In the case of the Fourth Eclogue, the pagan text is coordinated with biblical texts, making the Statius episode “a high-density meditation on both biblical and classical textual transmission” (“Only Historicize,” p. 46).

First Virgilio wonders how Stazio, a poet of great wisdom, could have sinned of avarice. Stazio is bemused at the very idea: avarice was too far removed from him! Stazio explains that his sin was prodigality, and that he was saved from damnation as a prodigal by a passage in Aeneid 3, which he cites in explanation. This passage in Aeneid 3 (for which see the attached document “Dante’s Vergil”) taught Stazio that prodigality is as grievous a sin as avarice. This point in itself is less than straightforward, because Dante himself effectively makes prodigality less grievous than avarice by making it clear that a soul of Stazio’s caliber could not be guilty of avarice.

If Stazio’s status as a prodigal is not straightforward, the interpretation of the citation from Aeneid 3 is even less so. The reference is complicated and has generated controversy for centuries, mostly because many scholars were reluctant to think in terms of a deliberate mistranslation. I think there is no doubt that Dante deliberately mistranslates the Aeneid here, in order to turn it to providential ends. In other words, the citation of Aeneid 3 in Purgatorio 22 is an example of Dantean providential mistranslation.

The second question is: how did Stazio convert to Christianity? How did he not end up in Limbo, with the rafts of classical poets named later in this canto? For, in effect, Purgatorio 22 also offers us an alter-Limbo, an addendum to Inferno 4. The answer comes in the form of another citation from another of Vergil’s texts: Stazio recites in Italian the verses from Vergil’s Fourth Eclogue that celebrate the birth of a boy who will be a savior and that were held in the Middle Ages to be prophetic of the coming of Christ. Here we have not a providential mistranslation but a correct translation of a Vergilian text.

To be clear, Dante provides a correct translation of the Fourth Eclogue but not a correct interpretation. Vergil was not referring to the birth of Christ, but to the birth of a boy whose identity has been debated but who was likely the son of a current Roman grandee.

In Dante’s account, therefore, damned Virgilio helped Stazio reach Christian salvation in two ways and each time through the medium of one of his own texts. He saved him from being damned for prodigality through the salvific message regarding the “sacred hunger for gold” of Aeneid 3. Through his Fourth Eclogue, Virgilio also saved Stazio from the default damnation that would have overtaken him if he had been completely virtuous but — like Virgilio himself — unbaptized and non-Christian.

Thus, Virgilio not only made a poet of Stazio, as we learned in Purgatorio 21, he also made him a Christian: “per te poeta fui, per te cristiano” (Purg. 22.73).

With respect to these Vergilian texts and their salvific effects we should add the following distinction: the construal of Aeneid 3 as a warning against prodigality is entirely Dante’s invention, requiring mistranslation, while the belief in the Fourth Eclogue as a prophecy of the birth of Christ was widely disseminated and accepted.

Moreover, Dante coordinates the effects of the Fourth Eclogue with the transmission of the Gospels in the case of Stazio. He specifically adds that Stazio was exposed to the Gospels, “disseminated by the messengers of the eternal kingdom” (Purg. 22.77-78):

Statius explains his conversion to Christ by pointing to the consonance he experienced between Vergil’s Fourth Eclogue and the newly disseminated words of the apostles: in contrast to the man on the banks of the Indus, he experienced the true faith because it was “seminata / per li messaggi dell’etterno regno” (Purg. 22.77–78). (“Only Historicize,” p. 47)

This point about Statius’s exposure to the Gospels also makes the issue of his birth date relevant. Statius was born circa 45 CE and died circa 96 CE. In other words, he lived entirely after the death of Christ, making his exposure to the circulating Gospels plausible. The issue of the transmission of ideas, and the injustice of holding accountable those who were not exposed to salvific messages, is one that Dante treats in Inferno 4 and again here in Purgatorio 22.

Let us consider too the varieties of Dante’s saved pagans: while the salvation of Cato and Stazio, for instance, is entirely Dante’s invention, the salvation of the Emperor Trajan, whom we will find blessed in Dante’s heaven of justice (and for whom see the third bas-relief in Purgatorio 10) was a widely circulated legend. It was believed that Gregory the Great prayed for the soul of Trajan and brought him back to life long enough for him to convert to Christianity so that he could die the second time a Christian. In this way, Dante uses popular culture to lend credibility to his own personal inventions.

The travelers, who are now three rather than two, because Stazio has become one of their number (see Dante’s Poets for the story of how the epithets that have been used heretofore exclusively for Virgilio, like “poeta”, are now used for Stazio as well), reach the terrace of gluttony. Here they encounter a strange tree from which a voice recites the examples of temperance. Purgatorio 22, a canto that is saturated in classical textuality and culture, ends by reaffirming biblical teachings. The golden age of classical antiquity, when acorns were delicious, is aligned with the experience of John the Baptist in the wilderness, when the saint nourished himself on locusts, “as, in the Gospel, is made plain to you”: “quanto per lo Vangelio v’è aperto” (Purg. 22.154).

The canto in which two Vergilian texts are shown to have covertly functioned like Gospels in achieving the salvation of one pagan, Statius, thus ends with a reference to the actual Gospel. An actual Gospel that is — for fortunate Christians — made manifest, declared, open: “aperto” (154).

Return to top

Return to top