Now that we have been “joined with the first star” — “congiunti con la prima stella” (Par. 2.30) — and are in the heaven of the moon, we are ready to experience our first encounter with a blessed soul. In this canto Dante will meet Piccarda Donati. She is the sister of Forese Donati, the old friend from Florence with whom Dante had a nostalgic interaction on Purgatory’s terrace of gluttony.

Forese died in 1296. For Piccarda we have less precise information. She was born in the middle of the thirteenth century and died at the end of the thirteenth century. Dante’s intimacy with Forese is such that, when he meets Forese on the terrace of gluttony in Purgatory, he asks his friend about the whereabouts of his sister:

«Ma dimmi, se tu sai, dov’è Piccarda; dimmi s’io veggio da notar persona tra questa gente che sì mi riguarda.» «La mia sorella, che tra bella e buona non so qual fosse più, triunfa lieta ne l’alto Olimpo già di sua corona.»(Purg.24.10-15)

“But tell me, if you can: where is Piccarda? And tell me if, among those staring at me, I can see any person I should note.” “My sister—and I know not whether she was greater in her goodness or her beauty— on high Olympus is in triumph; she rejoices in her crown already.”

Piccarda is “already in triumph in high Olympus” (Purg. 24.15) because, like her brother Forese, her death is very recent. Her position as already a blessed soul in Paradise betokens a very swift ascent up the mountain of Purgatory.

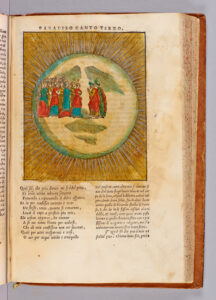

Despite her swift ascent through Purgatory, Piccarda’s location in Paradise seems (literally) inferior. There appear to be lower and higher heavens in Paradise, heavens that are therefore farther from and closer to God, and we meet Piccarda in the lowest heaven (also the slowest heaven, because the heavens move more speedily as they get closer to God and to the Empyrean). It seems to be incontrovertibly the case that if one is in “la spera più tarda” (the slowest sphere [Par. 3.51]), as Piccarda describes her home, one is in the least valuable celestial real estate.

Beatrice explains to the pilgrim that these souls are “relegated” here — a strong choice of verb that does nothing to minimize our developing sense of a lower order of bliss — because of unfulfilled vows:

vere sustanze son ciò che tu vedi, qui rilegate per manco di voto. (Par. 3.29-30)

what you are seeing are true substances, placed here because their vows were not fulfilled.

The verb relegare is defined in the Hoepli Dizionario thus: “Obbligare qualcuno ad allontanarsi dal luogo dove abitualmente vive per andare in un altro luogo lontano e sgradito; esiliare, confinare” (oblige someone to move far away from their habitual place to a place that is far off and unappealing; to exile).

We will learn in Paradiso 9 that the first three heavens are shadowed by the earth, and the result is that the souls of these heavens are characterized negatively: they comprise those who did not fulfill their vows (moon), those who lived with too much earthly ambition (Mercury), and those with too great an inclination toward eros (Venus).

Piccarda’s language stresses her lowliness, prompting Dante-pilgrim to ask a naive but profoundly important question. It is an important question because it returns to and rearticulates the paradox of the One and the Many that governs the Paradiso, as expressed in the cantica’s opening terzina. As we remember, the glory of the mover of all things penetrates a “Uni-verse” that is by definition One. And yet that glory penetrates differentially, “in una parte più e meno altrove” (in one part more and in another less [Par. 1.3]).

So now Dante-pilgrim asks Piccarda whether she experiences unhappiness at being so far from God, in the lowest of the heavens. Does she want a higher place? Does she want a higher place where she can see more? Does she want a higher place where she could be more “friends” with God? The childlike simplicity of the pilgrim’s language only adds to the potency of the questions:

Ma dimmi: voi che siete qui felici, disiderate voi più alto loco per più vedere e per più farvi amici? (Par. 3.64-66)

But tell me: though you’re happy here, do you desire a higher place in order to see more and to be still more close to Him?

These are questions that bring to the surface all our unspoken concern about unfairness continuing on into the realm of justice itself.

Ambivalence about one’s position in a hierarchy is a feature of human nature, and it is consequently a feature of discussions of Paradise. The poet of the Middle English poem, Pearl, written in the fourteenth century, shows his concern with rank in heaven in his recurrent use of the adverbs “more” and “less,” reminiscent of Dante’s “più” and “meno”: “Then the less, the more remuneration, / And ever alike, the less, the more” (10.5); “‘Of more and less,’ she answered straight, / ‘In the Kingdom of God, no risk obtains’” (11.1; trans. Marie Borroff, Pearl [New York: Norton, 1977]).

Dante explicitly raises the issue of envy among the saints in Paradise in the his philosophical treatise Convivio, explaining that there is no envy in Heaven because each soul reaches the limit of his personal beatitude: “E questa è la ragione per che li Santi non hanno tra loro invidia, però che ciascuno aggiugne lo fine del suo desiderio, lo quale desiderio è colla bontà della natura misurato” (This is the reason why the saints do not envy one another, because each attains to the end of his desire, which desire is proportionate to the nature of his goodness [Conv. 3.15.10]).

The above passage from Convivio offers a very precise gloss on the situation that Dante dramatizes in Paradiso 3, starring the Florentine Piccarda Donati. Placed by Dante in the lowest and slowest sphere, the heaven of the moon, and queried by the pilgrim as to whether her position is not a source of envy, Piccarda will explain that she feels no envy because she “has attained to the end of her desire, which desire is proportionate to the nature of her goodness”.

Modern imaginings of heaven, according to Carol Zaleski, have removed the problem of envy: “For many people in our own day, however, the plurality of heavens seems at last to have lost its rationale; the very notion of ranking souls offends democratic instincts” (Otherworld Journeys, 60; see Coordinated Reading).

If nowadays the “very notion of ranking souls offends democratic instincts”, it is worth noting that Dante stages his question to Piccarda precisely as a means of dramatizing the possibility of taking offense at souls being ranked from lowest to highest. But Piccarda does not rise to the bait. Rather, the pilgrim’s question gives Piccarda the opportunity to explain that heaven is a place where one’s desire is always satisfied, where desire cannot possibly exceed the measure of what one has, and where it is always aligned with the will of the transcendent power.

In other words, the souls of Paradise are completely happy with the grace that is apportioned to them:

E ’n la sua volontade è nostra pace: ell’è quel mare al qual tutto si move ciò ch’ella cria o che natura face. (Par. 3.85-87)

And in His will there is our peace: that sea to which all beings move—the beings He creates or nature makes—such is His will.

Dante-poet scripts this dialogue as a model of ambivalence, in the etymological sense of allowing two different positions to materialize and to receive equal value. He is trying to dramatize the two prongs of his paradox as delineated in Paradiso 1.1-3: the irreducible difference of the souls — the fact that they are “vere sustanze” (true substances) as Piccarda says in Paradiso 3.29 — can only be expressed via hierarchy, and yet the concept of hierarchy is in apparent contradiction with the concepts of unity and similitude.

This contradiction is forcefully expressed in the narrator’s summation of what he learned from Piccarda, where the crude Latinism “etsi” — “although” — pivots the syntax and the poet’s thought away from unity and towards difference:

Chiaro mi fu allor come ogne dove in cielo è paradiso, etsi la grazia del sommo ben d’un modo non vi piove. (Par. 3.88-90)

Then it was clear to me how every place in Heaven is in Paradise, though grace does not rain equally from the High Good.

In The Undivine Comedy I comment on the above terzina thus:

Everywhere in heaven is paradise, i.e., all heavenly locations are equally good; nonetheless, at the same time, grace is not equally distributed. This is a notion we can accept only if we cease to think in terms of space; otherwise, we run into the problem of all celestial real estate being equally valued despite not receiving the same goods and services. Moreover, if grace is not distributed d’un modo (a phrase that doubles in the Paradiso for igualmente), then it must perforce be distributed più e meno. And so we return to the paradox of the Paradiso’s first tercet, which Dante does not so much attempt to resolve as hold up for scrutiny, perusing it first from one perspective and then from another. Given that the problem of the one and the many is not one that Dante can, in fact, “resolve,” we nonetheless may note that our poet seems more to revel in it than to want to cover it over. (p 183)

The latter part of Paradiso 3 contains Piccarda’s poignant story of having been violently kidnapped from the cloister by the men of her brother Corso Donati. Her story is thus a story not of simple violence, but of Florentine political violence. Corso was the leader of the political faction of the Neri (the faction that exiled Dante); he wanted to give his sister in dynastic marriage in furtherance of his quest for alliance and political power. Piccarda also introduces the Empress Costanza, mother of Frederick II, who like her had joined the order of Santa Chiara but was forced to leave for an even higher dynastic calling.

There is much in this story that echoes the story of Francesca, especially in that both women experienced the typical destiny of upper-class women: they became pawns in dynastic marriages. Francesca committed adultery with her husband’s brother, and her marriage ended in uxoricide — as did the marriage of Pia dei Tolomei in Purgatorio 5. We note the common theme here, and sense Dante’s interest in denouncing the injustice of dynastic marriage and the many ways in which the practice victimizes women. On this topic, see my entry “Dante Alighieri” in Women and Gender in Medieval Europe: An Encyclopedia, and “Dante and Francesca da Rimini: Realpolitik, Romance, and Gender”, cited in Coordinated Reading.

Piccarda refers to the “sweet cloister” from which she was abducted by violent men: “Uomini poi, a mal più ch’a bene usi, / fuor mi rapiron de la dolce chiostra” (Then men more used to malice than to good took me — violently — from my sweet cloister [Par. 3.106-7]). Her language is not a cultural anomaly; historians teach us that the cloister was for many upper-class women a desirable alternative to marriage.

Piccarda describes being forced — compelled against her will — to leave the cloister. The compulsion that she says she experienced will be a major theme of the next canto. Did she experience compulsion or did she not? Can her departure from the cloister ultimately be understood as truly involuntary?

Return to top

Return to top