As discussed in the Commento on Purgatorio 10, there are three canti devoted to the terrace of pride and they are symmetrically and neatly arranged: Purgatorio 10 treats the examples of the virtue of humility; Purgatorio 11 treats meetings with three souls who exemplify three kinds of pride; and Purgatorio 12 treats the examples of the vice of pride.

As the central of the three canti devoted to pride, Purgatorio 11 begins with the recitation of the Lord’s Prayer, the only prayer inscribed fully into the Commedia. It is interesting to note the ways in which Dante effectively “rewrites” the Lord’s prayer, making it in some way a Dantean gloss of the Scriptural verses. Although the glosses are exhortations to humility, the poet’s act of rewriting the Lord’s Prayer seems precariously close to prideful, another form of the “Arachnean art of the terrace of pride” discussed in Chapter 6 of The Undivine Comedy.

The pilgrim meets three souls in Purgatorio 11, who exemplify three kinds of pride: Omberto Aldobrandeschi, a great noble from the Maremma region who exemplifies pride of family and lineage (see Purgatorio 8 and especially the encounter with Currado Malaspina for these issues); Oderisi da Gubbio, a miniaturist who exemplifies pride in art and in human endeavor; and Provenzan Salvani, a Sienese man of power and head of the Ghibellines, who exemplifies pride of power.

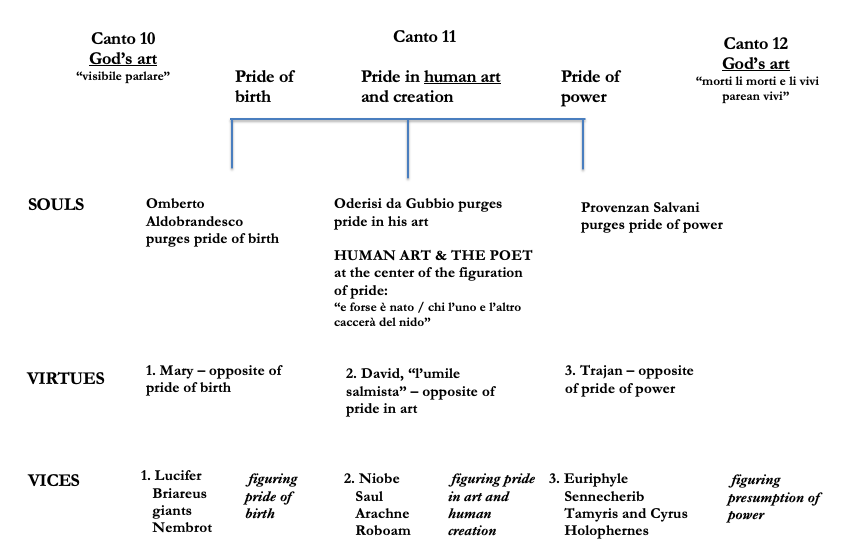

The below chart of the terrace of pride maps the three types of pride — pride of family, pride of art, and pride of power — onto the three structural components: the examples of the virtues, the souls, and the examples of the vices.

There are three canti devoted to the terrace of pride, and there are three prideful souls purging the sin of pride in the central canto, Purgatorio 11. Thus, the core of the terrace of pride is the core of the central canto, Purgatorio 11. At the core of the terrace of pride, we find the artist Oderisi da Gubbio, who is the second of the three souls who are featured in the second canto of the triad devoted to this vice. Pride in art or vainglory is thus the poet’s central concern.

Before considering what Oderisi has to say, let us note that he constitutes another of the friends whom Dante places in his Purgatory: Oderisi follows Casella, Belacqua, and Nino Visconti in this group, and looks forward to Forese Donati. Oderisi sees Dante and recognizes him, displaying his passionate desire to speak with him:

e videmi e conobbemi e chiamava, tenendo li occhi con fatica fisi a me che tutto chin con loro andava. (Purg. 11.76-78)

he saw and knew me and called out to me, fixing his eyes on me laboriously as I, completely hunched, walked on with them.

Oderisi speaks on the vanity of all earthly things, including artistic supremacy. There is no point in being prideful as an artist, he says, because ultimately everything passes, no human art endures, and all great artists are eclipsed by their successors. As his examples of surpassed artists, Oderisi offers first visual artists, Cimabue who is eclipsed by Giotto, and then verbal artists, Guido Guinizzelli who is eclipsed by Guido Cavalcanti in the “gloria de la lingua” (glory of our tongue [Purg. 11.98]). And both Guidos will in turn be eclipsed by one “who will chase both out of the nest”:

Credette Cimabue ne la pittura tener lo campo, e ora ha Giotto il grido, sì che la fama di colui è scura: così ha tolto l’uno a l’altro Guido la gloria de la lingua; e forse è nato chi l’uno e l’altro caccerà del nido. (Purg. 11.94-99)

In painting Cimabue thought he held the field, and now it’s Giotto they acclaim — the former only keeps a shadowed fame. So did one Guido, from the other, wrest the glory of our tongue—and he perhaps is born who will chase both out of the nest.

Who is the one who will chase Guido Guinizzelli and Guido Cavalcanti from the nest? Oderisi’s lesson in humility is here compromised by what is certainly a veiled reference to Dante himself: the poet who will supersede and surpass both Guido Guinizzelli and Guido Cavalcanti.

And so, matters are not quite so simple as a straightforward lesson in humility. The dialectical thrust of the above passage is replicated in this next passage, where the vanity of all earthly achievements is proposed again, framed in a linguistic fashion this time, through the following rhetorical question:

Che voce avrai tu più, se vecchia scindi da te la carne, che se fossi morto anzi che tu lasciassi il ‘pappo’ e ’l ‘dindi’, pria che passin mill’anni? ch’è più corto spazio a l’etterno, ch’un muover di ciglia al cerchio che più tardi in cielo è torto. (Purg. 11.103-08)

Before a thousand years have passed — a span that, for eternity, is less space than an eyeblink for the slowest sphere in heaven — would you find greater glory if you left your flesh when it was old than if your death had come before your infant words were spent?

To the question — what glory will you have in 1000 years? — the correct answer in the key of humility is “none”: in 1000 years it will no longer matter whether you die an infant, whose only words are “pappo” and “dindi” (Purg. 11.105), or whether you live to old age.

And yet, and yet . . . I write this on the verge of 2015, which will be the 750th anniversary of Dante’s birth in 1265: already three-quarters of the way to 1000 years. And Dante’s words still live. And, despite Oderisi’s claim that “La vostra nominanza è color d’erba, / che viene e va” (Your glory wears the color of the grass that comes and goes [Purg. 11.115-16]), Dante’s nominanza — his name, his cultural Q score — remains, in Ovid’s word, indelebile.

Return to top

Return to top